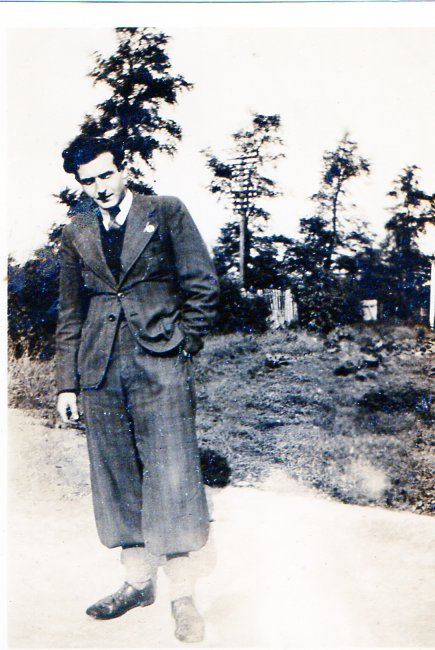

Looking steadfastly into the distance, this cover photograph on the school's prospectus illustrates the vision the founders had for their refugee pupils. A vision looking to the future, a future spent in Palestine or in the 'British dominions and colonies and South America".

[courtesy of Yanky Fachler]

PLEASE NOTE - A CONTACT POINT FOR THOSE WISHING TO APPEAL FOR INFORMATION ABOUT A RELATIVE WHO ATTENDED WHITTINGEHAME FARM SCHOOL CAN BE FOUND AT THE END OF THIS PAGE.

Whittingehame Farm School

“Having one’s life saved, meant to be uprooted, to give up one’s sheltered home and family, to be dispossessed and be at the mercy of strangers, to feel helpless and unable to help those dear to us that were left behind.” Ester Golan, former pupil, March 1989.

Whittingehame House, west of Stenton, East Lothian.

A.J. Balfour

One of East Lothian’s grander buildings is Whittingehame House, birthplace and former home of A.J. Balfour. Balfour, raised to the peerage in 1922 as Earl of Balfour and Viscount Traprain of Whittingehame, held Cabinet office for twenty-seven years and was Prime Minister between 1902 and 1905. He is buried in the family plot nearby. Our interest in him focuses upon his period in office as Britain’s Foreign Secretary between 1916 and 1919. In 1917 British politicians’ thoughts were turning to the likely shape of the post-war world. The Ottoman, or Turkish, Empire was unlikely to survive the conflict and the fate of its extensive territories around the eastern Mediterranean was requiring attention. In August, Balfour drafted a letter of some future significance in his study at Whittingehame. This document, the 'Balfour Declaration' so called, was accepted by the British Cabinet and sent to Lord Rotheschild, a prominent member of the Jewish community on November 2nd. The Declaration was brief but potent and indicated British support for the creation of a Jewish “national home” in Palestine. It read:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

Whatever the subtle nuances of this document, whatever the controversies it created in the future and its significance at the time, this document forever linked the Balfour name to the Jewish cause. Jews had been the target of restrictions and persecution throughout the length and breadth of Europe since the Middle Ages. By no stretch of the imagination was anti-Semitism purely a German phenomenon but when Arthur Balfour died in 1930, he would have had little idea of the storm which was about to descend upon the Jewish people in Germany and ultimately across Europe. Few, if any, did.

When Hitler and his Nazis Party came to power in 1933, the active persecution of the Jewish people worsened and Jewish parents were increasingly left with the horrible dilemmas posed by how to deal with it: ultimately, whether to stay or to leave. However, leaving became increasingly more difficult, especially after the passing of the Nuremberg Laws in September 1935. Jews then faced almost insurmountable obstacles, since the Nazis made it increasingly costly and difficult to leave and other countries (including the UK) made it very difficult for refugees to come in. When opportunities to leave did present themselves, Jewish families were often faced with the horrible dilemma of whether to abandon their lives in their homeland of Germany or whether to send their children out alone. Many had little choice but to opt for the latter.

Aliyah and Whittingehame

In addition to the pressure to escape from Nazi Germany, many Jews held to the vision of Aliyah (the ascent), the emigration of Jews to Palestine. Strenuous efforts were made by some of the groups involved in the evacuation of Jewish children (known as Kindertransport) to prepare them for eventual emigration to Palestine and, according to Eli Fachler, the majority of pupils were in Whittingehame thanks to recommendations from the Youth Aliyah organisation itself.

Robert Arthur Lytton, 3rd Earl Balfour [Viscount Traprain in 1942]

Used under Creative Commons Licence, National Portrait Gallery

Whittingehame Farm School

When Balfour’s descendent, his nephew Robert Balfour, Viscount Traprain (later 3rd Earl Balfour), offered Whittingehame as a school for Jewish children, his offer was taken up gladly. The house, grounds and land sufficient for a farm were leased to The Whittingehame Farm School Ltd., a non-profit making organisation which aimed to educate and train Jewish children in the range of agricultural skills which would enable them to be useful contributors to both their British hosts and potentially to Jewish Palestine. Its chairman was Captain Robert Solomon. The school was co-educational and intended for some 150 - 170 children at a time. According to Countess Balfour, it housed and educated some three to four hundred children over its lifetime from January 1939 to September 1941. The initial intake was fifty-one and numbers varied as pupils left on attaining sixteen (perhaps seventeen). Normally boys outnumbered girls by two to one. Clearly getting the children (aged between fourteen and sixteen) into Whittingehame was one thing but being able to finance such an enterprise was another. A significant portion of the school’s prospectus was devoted to finance.

The Courier, the local East Lothian newspaper, reported the formation of the school and, some time later on Friday 24th February, 1939, it reported the arrival of the first contingent of twenty pupils under the wings of '…a German matron,' presumably Luci Laquer.

Note - Viscount Traprain joined the Royal Naval Reserve while his two sons attended Eton. All three were sometimes able to visit Whittingehame, Viscount Traprain when he was on leave and his sons when they were on holiday. Eli Fachler mentions that the boys would help with the harvest.

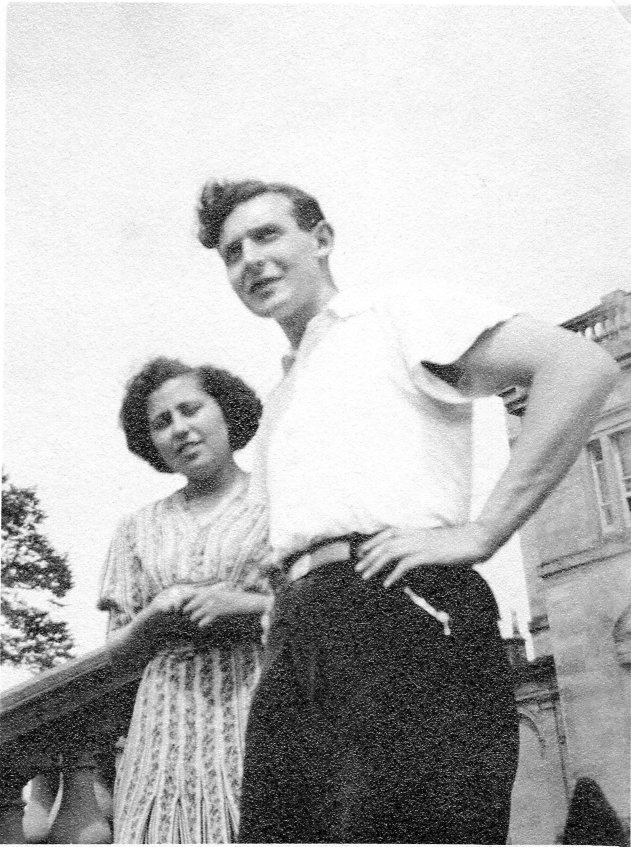

A group of Whittingehame School pupils

(Norbert Abeles back row extreme right, partially obscured. Eli Fachler extreme right)

Photographer - Farrington Drew.

Finance

A grant of £2,000 was given by a group called the Women’s’ Appeal Committee to cover equipment and any alterations to the building suggested by Douglas Miller in the surveyor’s report. The Council for German Jewry gave a limited financial guarantee enabling the initial setting up of the school to go ahead. Each pupil was estimated as costing £50 per annum for the two years of their stay and this was to come in the form of a £50 guarantee provided by individuals to cover each pupil. The running costs of the school were expected to be in the region of £10,000 per annum and again donors were to be found to covenant £12.50 quarterly or £50 per annum. This was likely to come mostly but not exclusively from Jewish families in the UK. The Secretary of the school had a London address in 31A, St James’s Square (and also in 14 Holland Park Road) and the school received its intake from Edinburgh or Dunbar via an organisation called the Movement for Child Refugees, in effect Kindertransport.

In its advertisements eye-catching headlines included “To the boy or girl refugee: you can help Britain in the most vital department of her war effort, in the production of food” and “To the guardian of a refugee child: agriculture, more than any other career, offers lasting prospects.”

Staff

At the early stage the list of staff was fairly vague, but the second headmaster was Charles Maxwell, M.A. The first head, Mr A. Corinth White, had only lasted a few weeks as he proved unsuited to the task, lacking sufficient control over the high-spirited children. His teaching style was too traditional to sit easily with such a polyglot group.

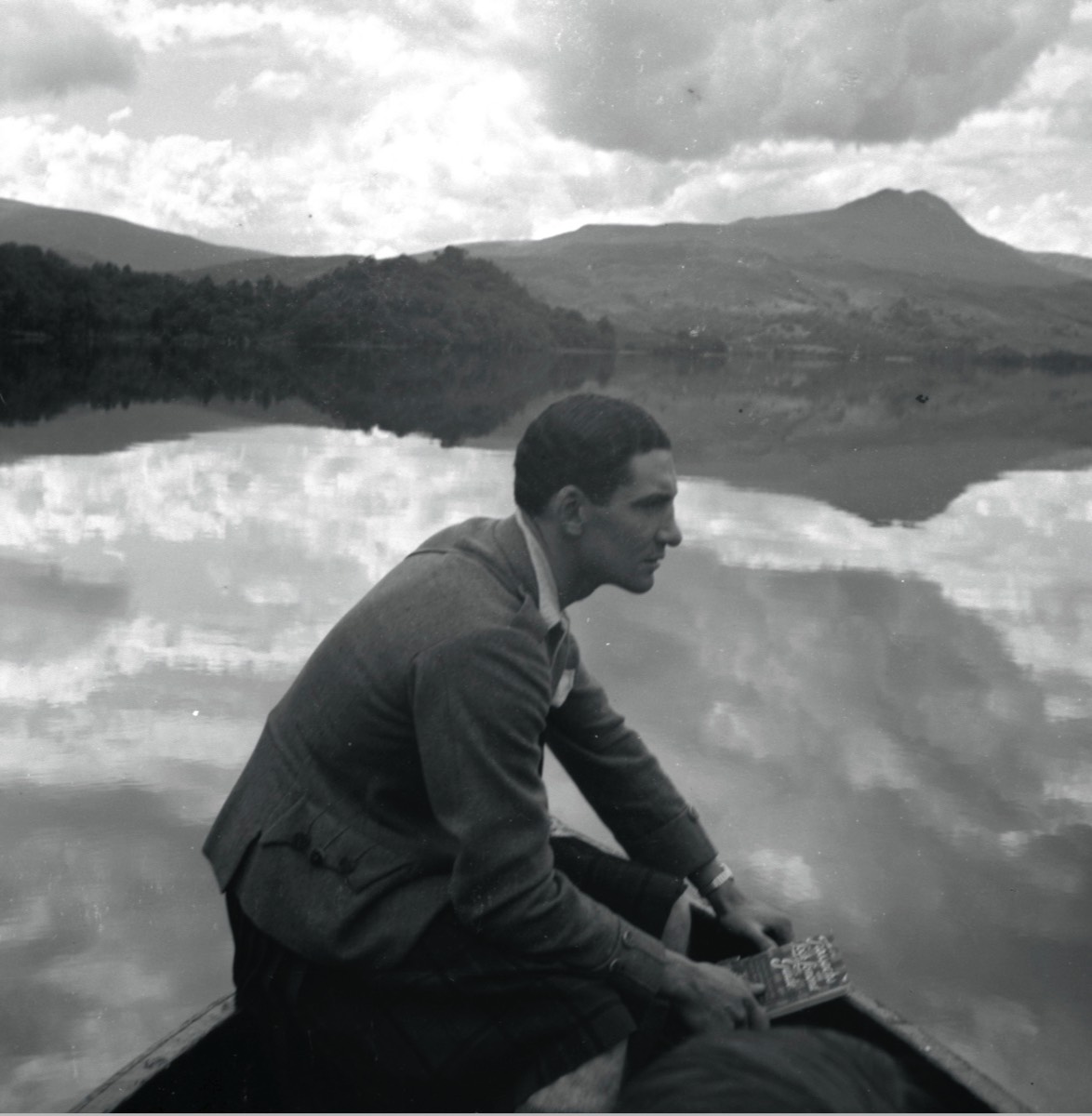

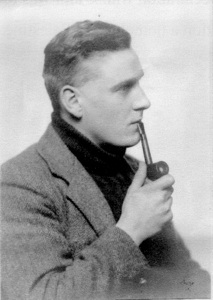

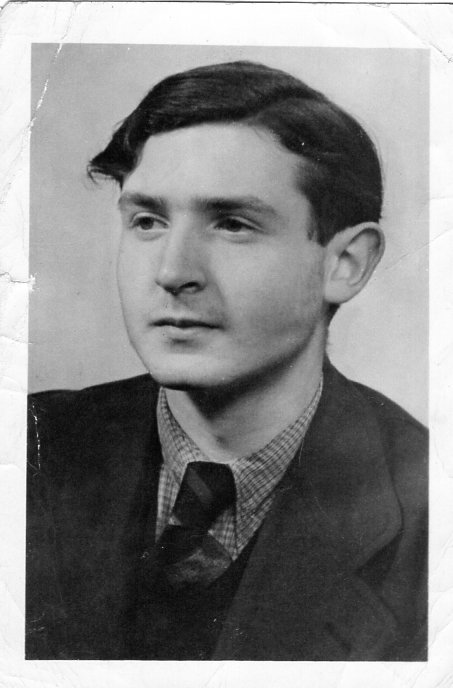

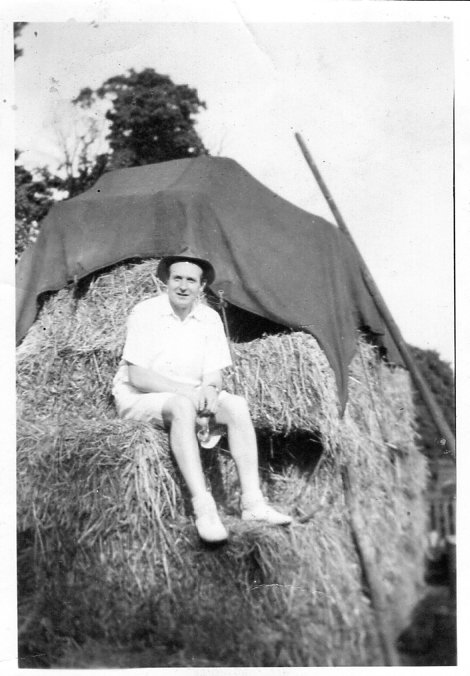

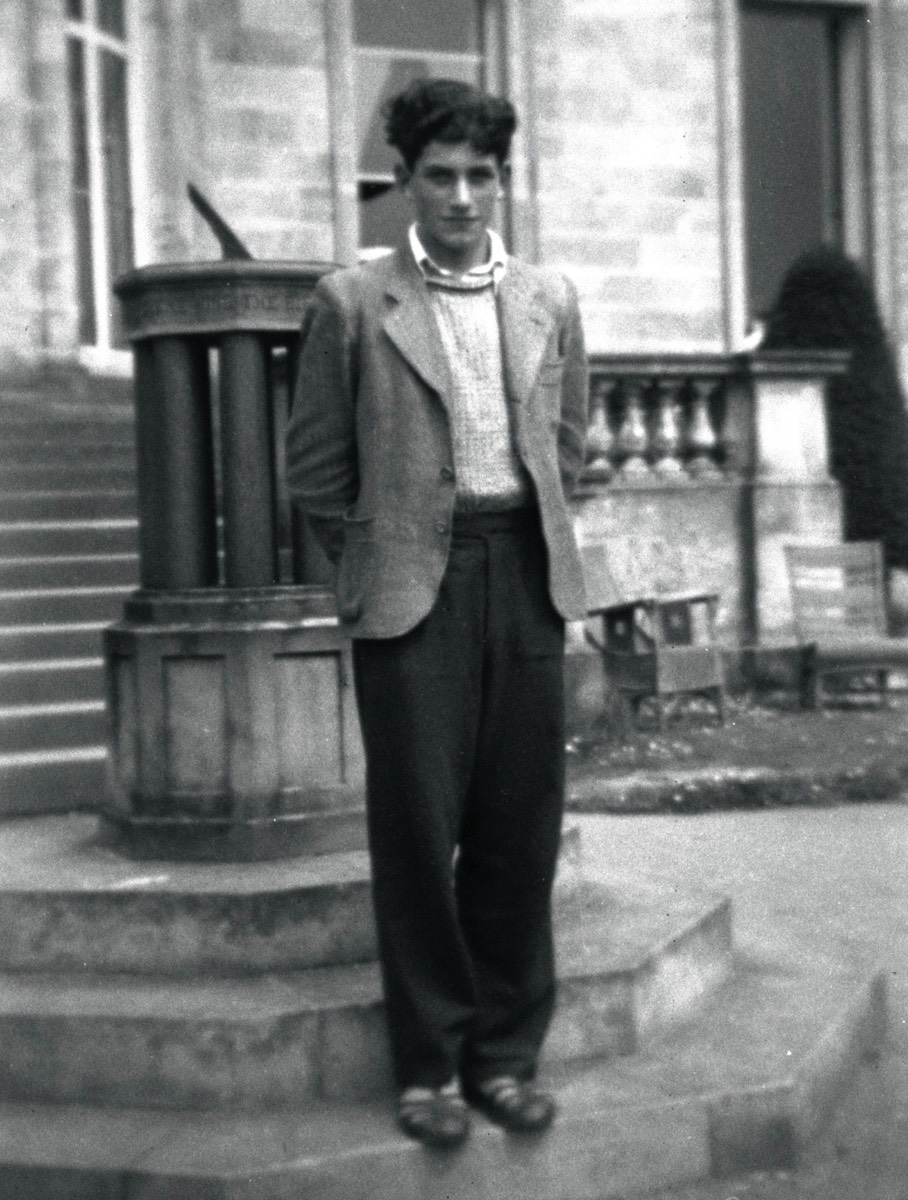

Charles R. Maxwell: Whittingehame’s second headmaster.

In military uniform in the two photographs above and

in the kilt on the right with a member of staff and pupils around the school's telescope.

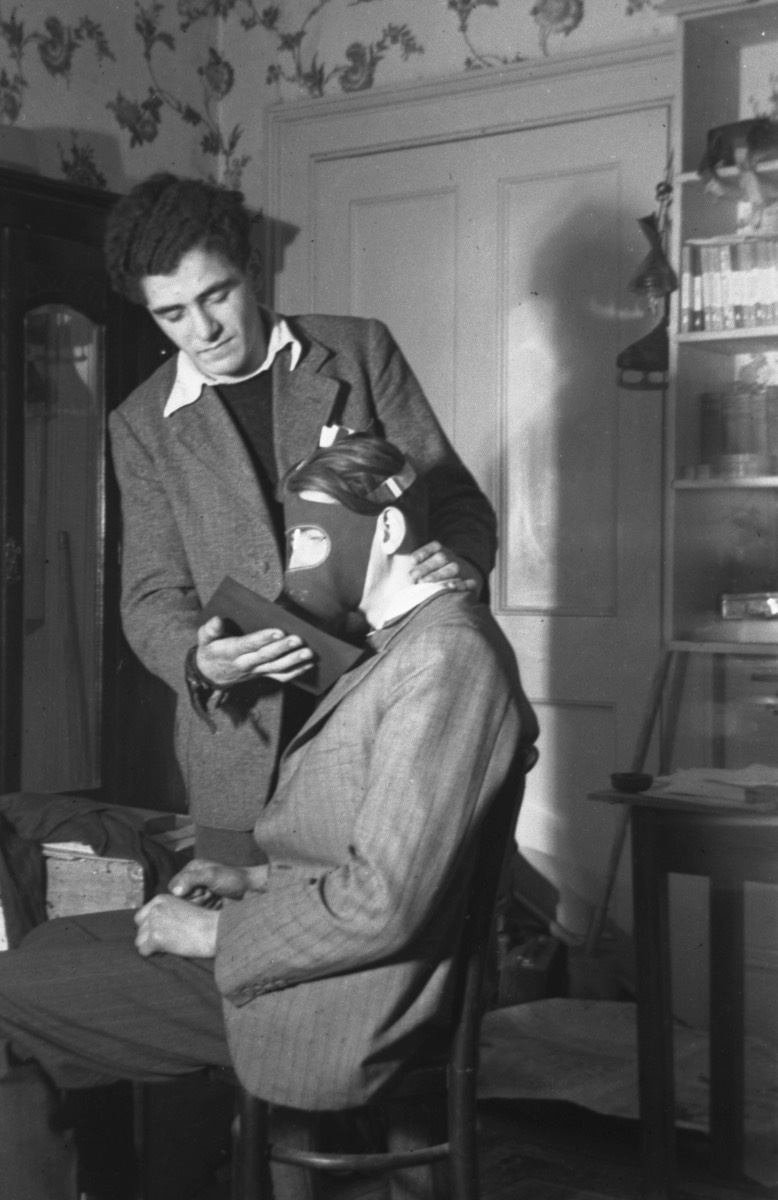

Further photographs of Maxwell. On the left he is pictured at table entertaining some of the pupils and on the right he is shown in contemplative mood on a lake.

- Two English masters.

- A German teacher of Hebrew and Religion.

- A Palestinian master ‘...especially qualified to teach vernacular Hebrew and agriculture’.

- A Mistress for biology and domestic science.

- A Mistress for horticulture and agriculture.

- A Matron and assistant matron.

- A qualified kitchen superintendent.

- A local doctor as Medical Superintendent.

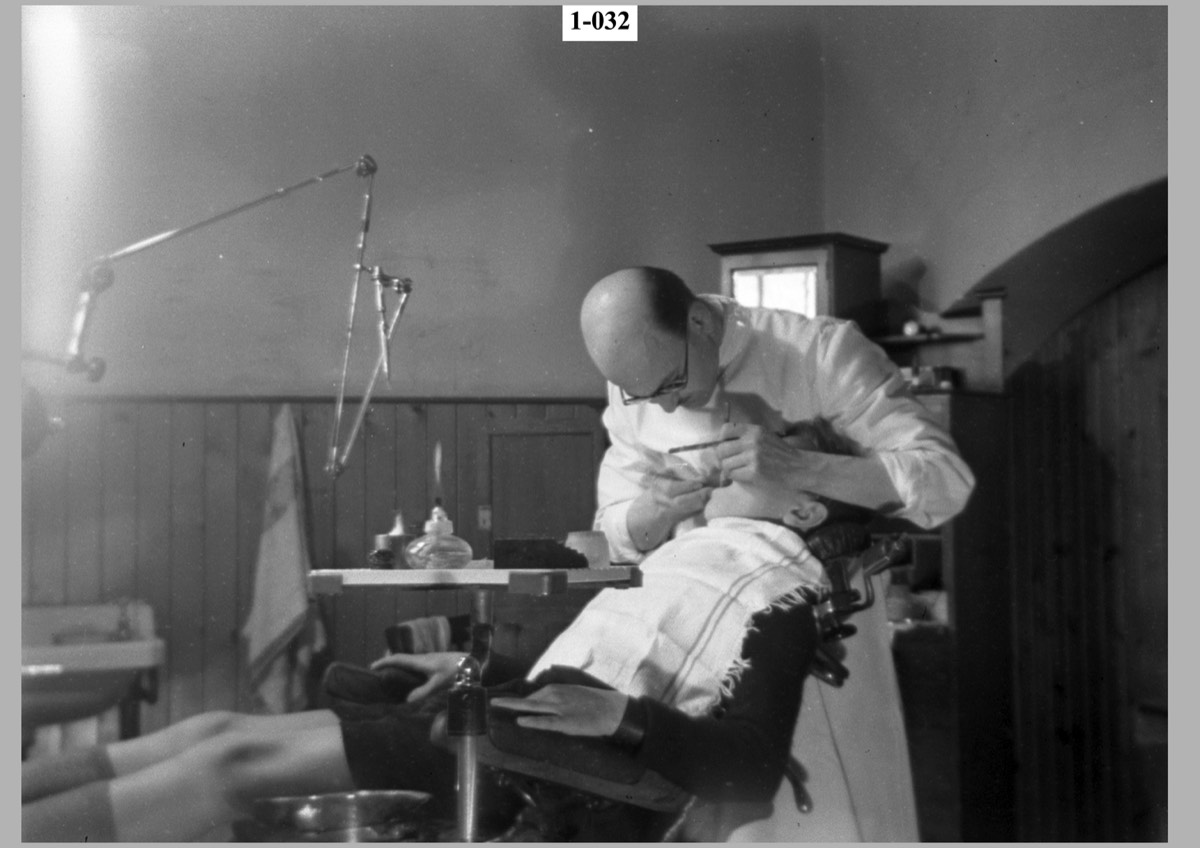

- A local dentist.

- Plus local farm bailiffs.

In the event the staff was a composition of British and refugee teachers. Names can be put to some of them:

- Mr Stegall: A Senior Master in the early days. He took all ID photographs and developed them with Norbert Abeles in a darkroom in a basement near Mr Coleman’s flat. He moved to another school and was replaced by

- Mr William Farrington Drew: Senior House Master and teacher of English and Maths.

- Miss Lucy Laquer: Matron (and also a refugee from Germany).

- Rabbi Joseph Hans Heinemann and Rabbi Torry Foerder: covered religious matters.

- Rev. Bernhard Cherrick: replaced Charles Maxwell as Headmaster and also gave lessons in Judaism.

- Mr Walters: was a Spanish teacher but taught English, as the former was not needed. He was a conscientious objector.

- Sidi Una-Levy: was the cook.

- Ruth Fischel: worked in the kitchen.

- Erich Duschinski: led a party of refugees from London to Whittingehame, became an assistant teacher and was a suitable translator as he spoke English, German, Hebrew and French. Was regarded as a Madrich.

- Miriam Piterkowski (formerly Mia Wimpfheimer): appears to have been an assistant teacher or Madrichah.

- Mr Gibbs: taught maths and English, was a friend of Mr Walters and stayed until called up for military service.

- Dr Salis Daiches: religious guidance.

- Mr Gilboa - taught modern Hebrew. Mentioned by Eli Fachler as having been an actor in Tel Aviv in the Ha-Ohel Theatre company.

- Mr Yaffe - taught modern Hebrew. Mentioned by Eli Fachler as having been a pupil of Bialik (the national poet of the Jews in Palestine).

- Yaakov Zerubavel - carpentery instructor from Feb. 1941. His wife, Ester, joined the domestic staff. Yaakov later became Head at Polton House.

- Mr Scharzmann - may have been partly responsible for agricultural instruction.

Others who may have been teachers but whose role/subject is unclear, included:

- Mr White.

- Miss Richards.

The staff was aided by many estate workers, by Lady Traprain, who was fondly remembered by many, and by Captain Spence of Haddington who helped with the formation of the school’s Boy Scout company. Two men with the same name, Cohen, one the head of Edinburgh’s Jewish community, and the other, smaller in build, aided the school. The latter owned a grocery store in Edinburgh and supplied Whittingehame Farm School with many of its needs. He "…took us under his wing”. (E. Golan)

According to Eli Fachler, Charles Maxwell was '..sacked…' in February 1940 and Lady Traprain took over as caretaker Head for six months. Given that Charles Maxwell is pictured above in uniform, another possibility is simply that he was called up for military service. Eli and he had 'form' and didn't see eye to eye. Eli, however, rather liked Lady Traprain and describes the dominant feature of her control as being '…quiet efficiency.' He wrote how she, '…invited groups of children for tea on a Sunday afternoon, and she did the rounds of the dormitories and the grounds with very human yet ladylike demeanour.'

Aims and organisation

Aims

The school prospectus was overtly supportive of the Zionist cause. It stated that ‘The general policy of the school is directed specially to fit the pupils for emigration to Palestine. The pupils have already commenced to arrange their lives, with the full approval of a sympathetic and understanding staff, on the model of the typical Palestinian settlement.” It continued: “In types and varieties the pupils are a cross section of continental Jewry, coming from rich and poor families, from orthodox and non-orthodox homes, from the best and worst schools of their hometowns. Their common tie is not alone the calamity that has overtaken them, but the even stronger one of hope - that one day they may assemble together not as refugees in a strange land but as proud and free citizens of the country of their dreams - Palestine.”

The prospectus continued by explaining that: “As [the pupils] leave this country on reaching the age of eighteen, the problem of their training is vitally important. They must be prepared for the difficult task of supporting themselves in strange lands. Trained land workers are the most welcomed immigrants to Palestine, the British Dominions and colonies and South America. The purpose of the Whittingehame Farm School is to provide, side by side with a general education, a thorough practical and scientific training in all branches of agriculture."

The Training

The syllabus was prepared with the help of Professor Shearer, Principal of the College of Agriculture of Edinburgh University, and with the keen involvement of Viscount Traprain and the course was designed to last two years. The prospectus outlined the general thrust of the elements covered as follows:

Agriculture

“Farm management, animal nutrition, live-stock, soils and manures, crops, use of farm implements, veterinary hygiene, dairy farming, poultry-keeping, agricultural science, agricultural botany, agricultural book-keeping and arithmetic, carpentry, motor mechanics, market gardening, dyke-building, marsh draining and elementary work in the smithy."

Horticulture

“Fruit, vegetables, flowers, pest and disease control, fruit and vegetable preservation, forestry, hedging, etc.”

A special effort was made to carry out instruction in English and Hebrew and was overseen by Dr Salis Daiches of Edinburgh. While theoretical elements were clearly present the over-arching emphasis was upon the practical.

The organisation of the school

Eli Fachler described the work done at Whittingehame as follows:

“In the long-established tradition of public schools, we were separated into Houses, each with its Housemaster. There were competitive games between the Houses, and friendly rivalry was evident in things like cleanliness awards.

The huge rooms of the mansion house had been transformed into dormitories, from two to ten children per dorm. There was the Boys Wing and the Girls Wing. Those members of the staff who were not Housemasters lived on or within walking distance of the estate. Some of the quarters were quite picturesque, like the one in the mill, which had been converted into the school laundry, filled with steam boilers, large hand-operated wringers, huge baskets and shelves.

Our Farm School was organised on a half-day work and half-day study basis. Our schedule began at seven in the morning, roll call followed by breakfast at 7.30. Some of us worked in the fields, others in the forests, the stables, the machine shop, the carpentry, the poultry houses, the cowsheds and the kitchen. I learned to drive a tractor and the combine harvester. …It was during my kitchen duty that I first learnt to bake and cook in catering quantities.”

Two staff members relaxing in Balfour’s study

Farrington Drew.

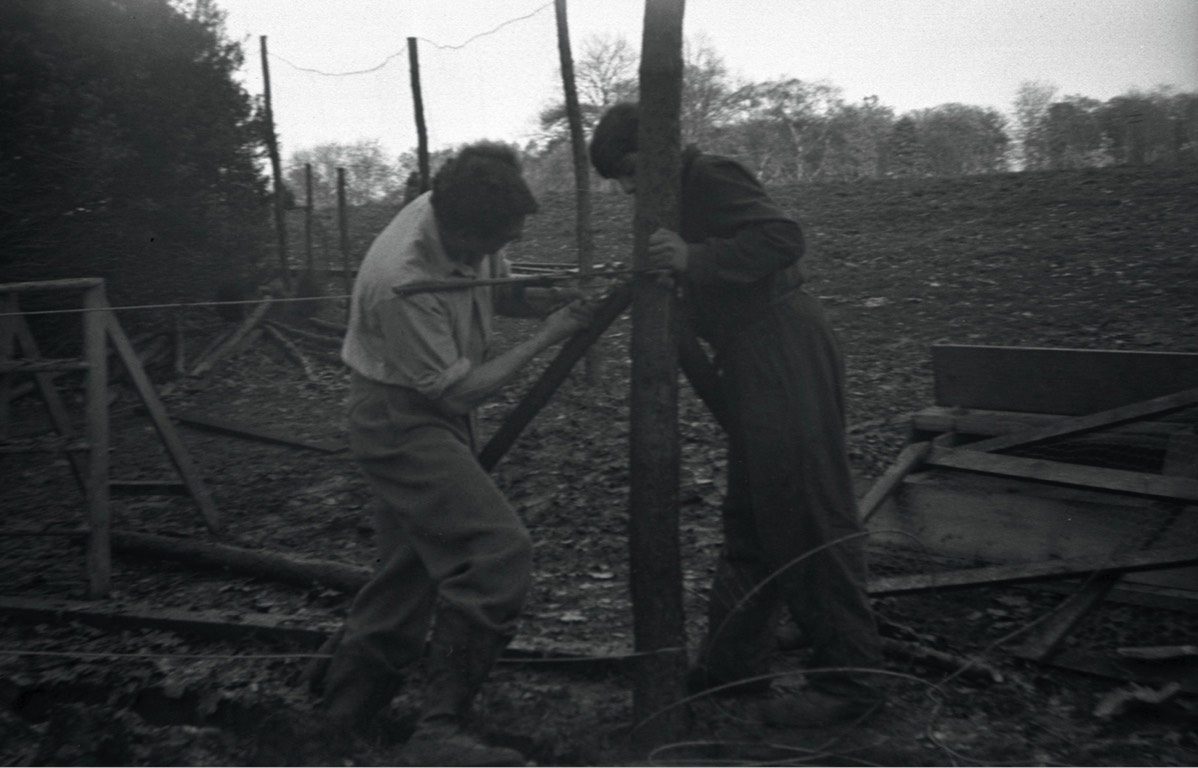

Work on the land

The following photographs show the pupils working

at their various practical farming tasks.

The young man leading the horse has been identified by Margaret Pollock as Peter Pollock.

Working in the classroom

In class: Eli Fachler sits with his yarmulke on his head.

The opening ceremony, 10th July 1939

The official opening of the school was sufficiently noteworthy to attract the attention of the Scotsman newspaper, which sent along a reporter. His report was later reprinted in the Jerusalem Times on the 17th July.

Before the opening ceremony and on everyone’s behalf, Captain R. B. Solomon placed a wreath on the grave of Lord Balfour.

The reporter took up the story of how the afternoon's ceremony unfolded. He wrote:

“ …A small company of boys and girls stood together on the level turf to the left of the mansion-house … [with] an audience of about six hundred on the lawn in front of them. The children, refugees from Germany, Austria and Czecho-Slovakia, sang one of the old Bible songs, ‘How beautiful are your tents, O Israel’. …

The musical programme made the afternoon specially memorable. …A large choir of the children - who were in their simple working attire - sang the Hebrew chorus, ‘Help the Nation.’ There are born musicians amongst them… A boy from Vienna took a series of vocal solos. His soprano voice, of exceptional quality and power, produced a moving effect.”

In addition to the musical elements, Eli Fachler, appearing in suitable costume, provided a dramatic rendition of Ezekiel xxxvii, including the passage ‘Behold, O my people, I will open your graves and cause you to come up out of your graves, and bring you to the land of Israel.’ The reporter described how Eli appeared in the: ‘…character and attire of the Prophet Ezekiel’, carrying ‘…a staff and with a light robe with belt and sandals, …’ and how he ‘…recited with dramatic gestures…’. It was all well received.

Another, un-named, boy stood up to describe the school’s organisation and daily work before Mr R. Cohen, from Edinburgh, spoke that he had been asked, on behalf of the Governors, ‘…to express their deep appreciation to their good friends, Lord and Lady Traprain.’ He commented that: ‘The Jewish people greatly appreciated what they had done.’

Lord Traprain answered in like vein, thanked the Governors for their kind gift of a Prayer Book and expressed the hope that the Farm School might be: ‘…to some degree [a means to help] to fit a section of the children who had been sorely oppressed [to] a future and better life in Palestine.’ The ceremony appears to have ended with the presentation of a bouquet to Lady Traprain by a female student.

[Thanks to the Scotsman newspaper]

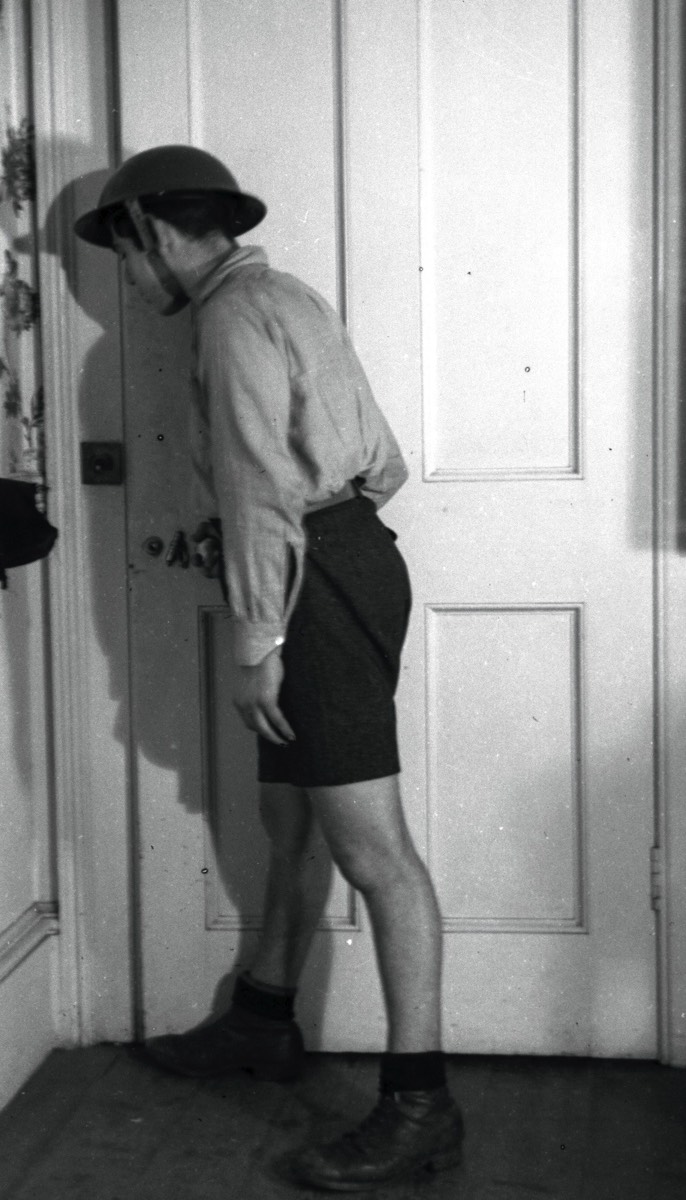

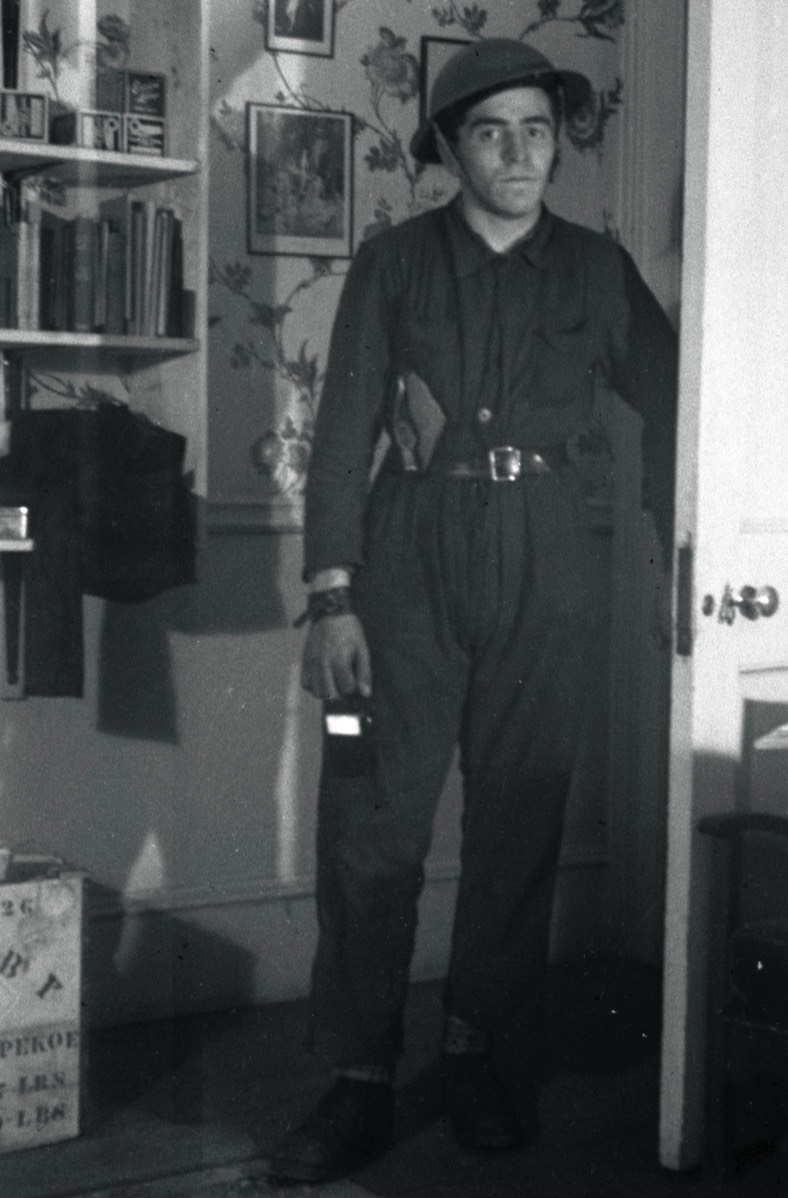

Born in Chalford, Gloucestershire and aged twenty-nine at the time, the Senior House Master and teacher of English was Dr William Farinton Drew. Known as "Rinton" by his family, he was a keen amateur photographer and by sheer luck his many photographs of life at Whittingehame Farm School have survived. Rinton joined the RAF in 1941 and was sadly lost out on patrol over the Atlantic on July 29th, 1943. His nephew, Dr Mike Challis, discovered the photographs and it is through his kindness and generosity that I am able to bring them to this wider audience. Both Mike and I would love to hear from anyone who recognises someone in these photographs. You can contact myself through the contact link at the bottom of this page.

Life At Whittingehame School

A number of sources allow us to glimpse what life was like for the Jewish exiles at the school set in the lovely soft countryside of East Lothian. When Rinton arrived at Whittingehame in August 1939 he wrote the following home:

“The journey was uneventful, except that...a storm travelled up with us. I had for companion the leader of the British Union of Fascists [Oswald Mosley] at Newcastle, who was just returning from a tour of Germany. His comments on Jewry were somewhat amusing in view of my destination.

Mr Maxwell met me at Dunbar. He is not a Jew but a Scotsman of the Clan Maxwell and met me wearing a kilt. [He] and the rest of the staff have done their best to make me at home and gave me a fine welcome. Mrs Maxwell (his mother) had breakfast for me and during this and after we discussed the arrangements.

I am here as Senior House Master, replacing Staggwell, ...who is going to a better post. Staggwell is staying on another two days to show me the ropes. He is a very pleasant chap and has shared the brunt from the early days. Apparently, the school opened last March (sic) with a Head (not Maxwell) and Staggwell as the English staff. The appointed Head made a mess of things and was sacked after three weeks and Maxwell immediately appointed in his place... and then for some months Maxwell and Staggwell carried on together as all the English staff doing the brunt of the work...and got on very well.

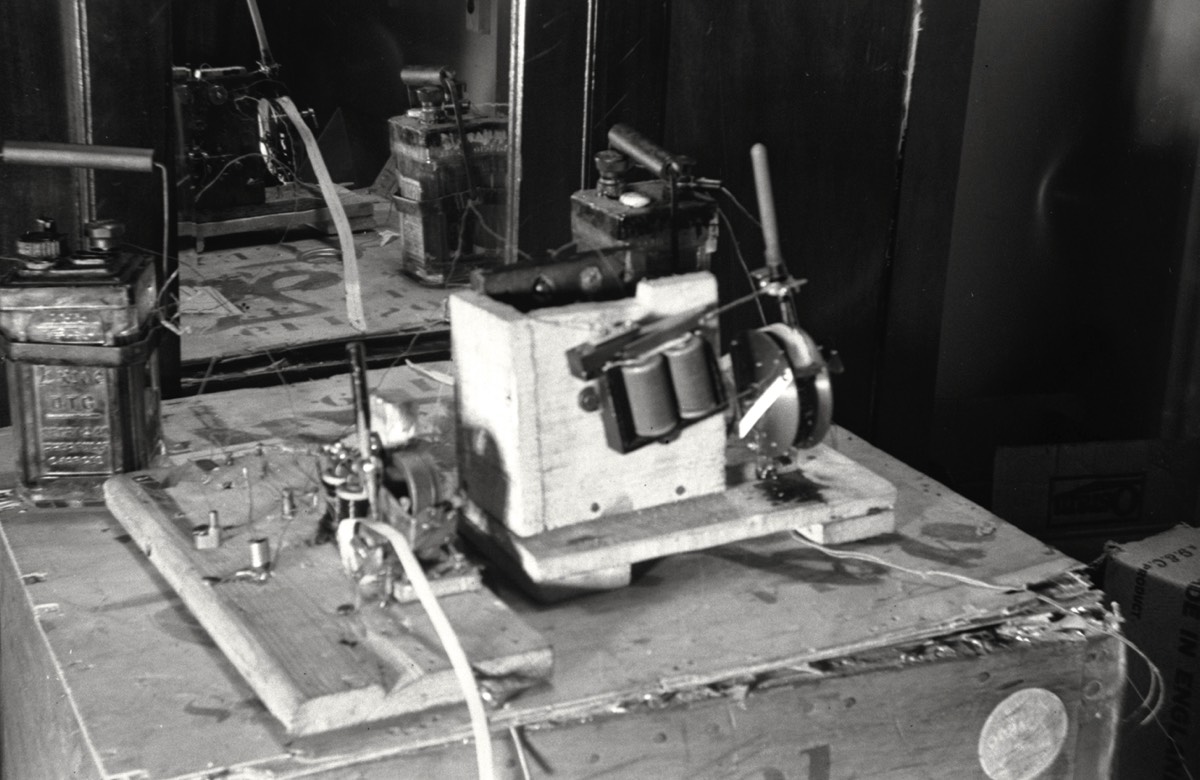

There is a very heavy Scots mist over everything today, so that I cannot see very far, but the lawns are beautifully kept up. The boys and girls run everything, the cleaning, washing, laundry, cooking, estate, everything. We have our own printing shop, boot repair shop, dental room (not run by the boys!) complete with electric drill; carpenter’s workshop where most of the things are made. I have an excellent little laboratory.... but things are very primitive in many respects...furniture is short...and it is a rather large place to furnish...there are 167 boys and girls here now.

The girls all wear long blue trousers or khaki shorts. The cooking at times leaves something to be desired apparently, from what I hear, since culinary disasters are rather apt to occur. The matron is German. All cooking is done on ranges, the original ones...and sometimes the fires don’t burn as they should.”

[My underlining]

“The boys and girls run everything”, wrote Rinton above. This appears to have been an accurate observation of life at Whittingehame. Both staff and pupil recollections support this view and Rinton's photographs bear this out. The pupils were clearly homesick, many of them aware that their chances of seeing their parents again were slim, but they were young, in youthful company, in the same boat and they were also aware of their good fortune in washing up in such lovely surroundings. Discipline at the school was, as always, that which the pupils themselves allowed and they appear to have seen off the first headmaster with some speed. His discipline was of the old school and his attire likewise and the pupils were not above laughing him out of his comfort zone and using ghosts and well-aimed water to emphasise their derision at his efforts.

As a first move, his replacement, Charles Maxwell, was moved to emphasise his intention of refusing to put up with any such nonsense. In the event he appears to have worked with the flow rather than against it. Apart from the necessary routine of the indoor and outdoor timetable, the pupils had considerable freedom to roam and contacts between them and the surrounding population took place in both sport and cultural activities.

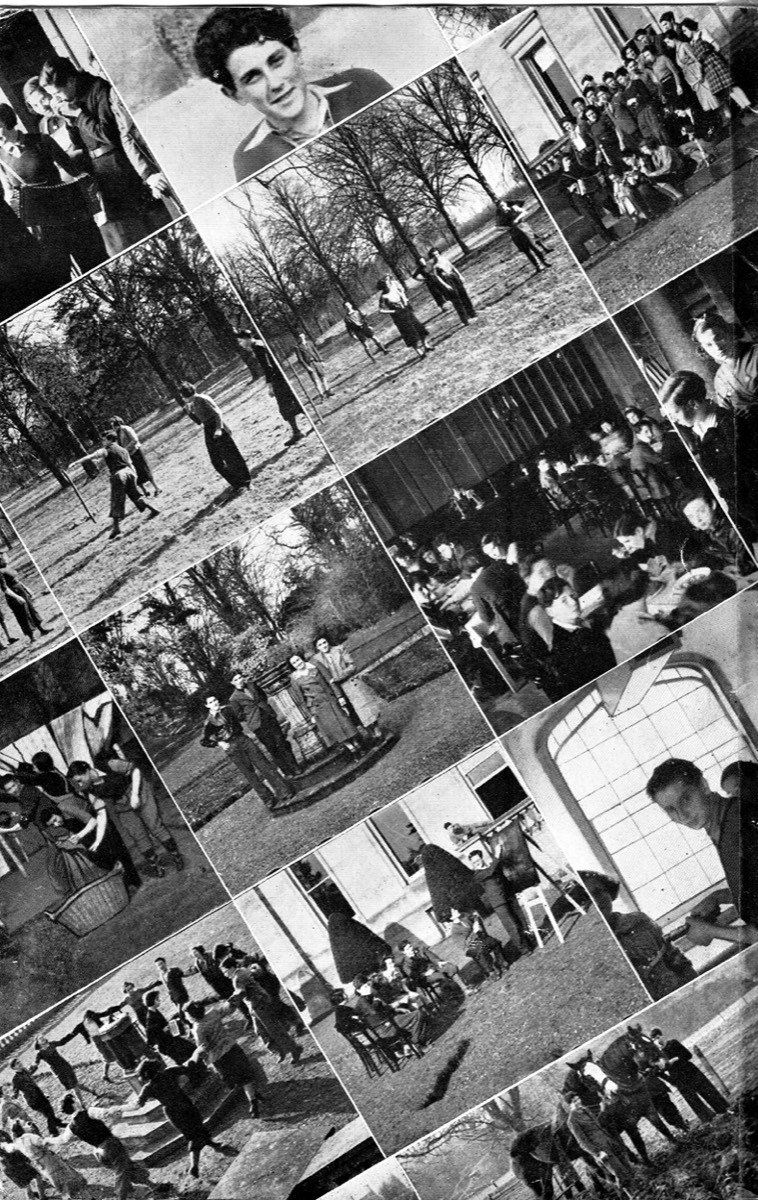

This shows the back page of the school prospectus. Clearly more photographs exist or existed than we have found. These give further tantalising snapshots of the variety of experiences the Jewish pupils experienced at Whittingehame.

[Courtesy of Yanky Fachler]

The boy in the centre photograph at the top has been identified by his daughter as Peter Heinz Pollak. The member of staff writing on the blackboard in the lower picture has been identified by Margaret Pollock as Eric Duschinsky.

Religious and political attitudes

He called this contingent, the ‘…most vocal and best educated.’ He went on: ‘They had lived and breathed the atmosphere of the class-conscious workers’ housing estates in Vienna that had been the scene of pitched battles with Fascists. They had seen their parents mount the barricades, they themselves had participated in street fighting and they were highly politicised. They were also indoctrinated with Communist dogma. To demonstrate their doctrines, they even had a picnic with a primitive barbeque outside the school grounds on Yom Kippur, about which they boasted with gusto.’

He amplified his views on the different political and religious views around him at Whittingehame Farm School. He wrote: ‘… We were all members of Zionist youth movements. Our inclusion in the Kindertransport programme probably owed as much to that as to anything else. My own group of friends were all from the Bachad group. Other youth groups represented in Whittingehame included Habonim, Hashomer Hatzair, Werkleute and others.

…It was only natural that we formed kvutzot (groups) based on our political orientation, mirroring the various political parties already active in Palestine. The names we gave these kvutzot reflected various kibbutz ideologies, such as Degania, Ein Charod or Tel-Chai.Threre was even a Scout group, led by one of the teachers who was the scoutmaster. The largest kvutzot, with about fifty members, was the religious group, of which my contingent of Bachad was the main core.’

Eli was chosen as the leader of his group, called Bilu (Bet Yaakov Lechu Vanelcha). His group asked for madrichim (counsellors) but it took time for some to arrive.

The newspaper

The political and religious undercurrents running through life in Whittingehame found open expression through the school’s newspaper. This, four to eight page news sheet, existed for the pupils to write about their ‘views, about art and culture, about their home life,’ and was pinned up on a notice-board for all to read. Eli relates how the Viennese contingent, 'True to Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist form,… exploited this medium, and even succeeded in converting some political and religious innocents to their cause.'! Eli didn't take this lying down and reposted through the medium of poetry. He wrote a poem which '…poked fun at them, emphasising their abysmal ignorance of all things Jewish, especially their lack of rudimentary Jewish history, and the contribution of the Jews to the glorious Bolshevik Revolution.' Eli was a fighter!

Pupils at Whittingehame School working in the fields.

Farrington Drew.

Two locals remember Whittingehame Farm School

Jean Coleman

Jean was the daughter of the Balfour’s butler. Apparently, the plan was for her family to move into Whittingehame House to act rather like caretakers as the Balfour family had moved to a smaller house nearby called Redcliff. They were to be there for five years but the five turned into twenty-seven! At first the house was furnished but gradually most of the furniture and accoutrements were sold off and Jean recalls that the house was pretty empty by the time the Jewish children arrived. Jean and her family lived ‘below stairs’ and she well remembers the pupils dancing so enthusiastically on the floor above her living-room that the ceiling came down - twice!

Her memories of the time of the school are limited but she recalls that the girls were housed on the top floor and the boys on the floor below. Apparently, some boys went out now and then with the fishermen from Dunbar and brought home lobsters which, at times, their faith forbade them to eat. Mr Drew and the other staff were really keen to taste them, so Jean’s mother cooked them in their kitchen. Jean was a Girl Guide and Eva, a pupil, came with her to the local Stenton Guides. The oath which all Guides had to take was specifically altered for this girl.

Ivan Clarke

Aged 15-16 at the time and the son of the farmer who farmed Eastfield Farm on the Whittingehame estate, Ivan remembers the Whittingehame refugees very well and described his initial contacts with the children as stemming from curiosity more than anything else, as he and his local friends tried to find out who these refugees from the Continent were. Ivan was quite a good footballer and standing watching on the touchline of the Whittingehame pitch one day, he was asked if he’d like to join in. This he willingly did and must have impressed because he continued to play on the Whittingehame team during many of the local matches. He remembers that the Captain was called Freddy, ‘...a lovely person.’ He also recalls playing Stenton and Garvald and a number of teams that came in buses.

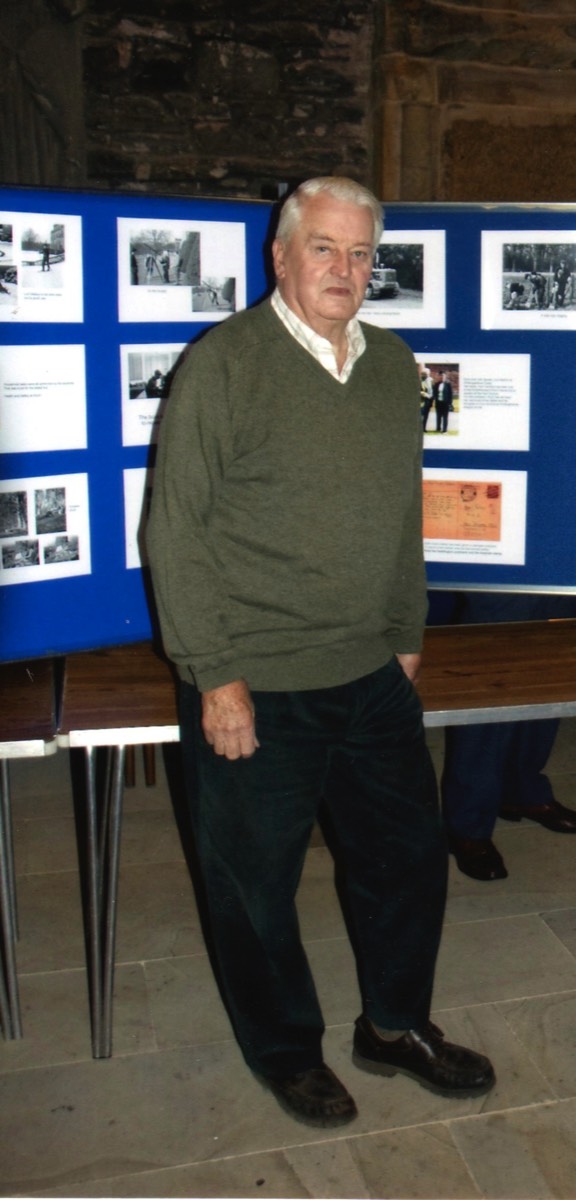

Ivan Clarke at an exhibition about Whittingehame

Farm School in St Mary’s, Haddington

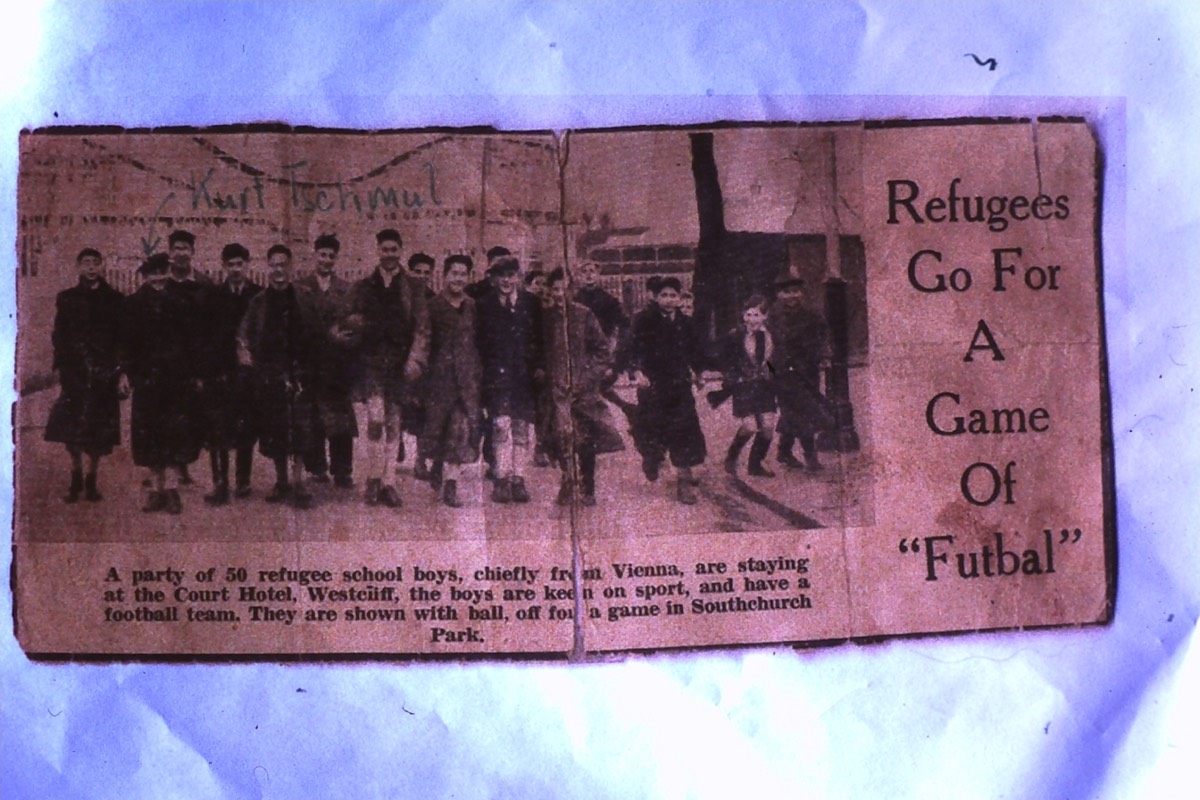

A bit of a puzzle - did the Whittngehame pupils really visit the south coast of England for a football match? Or, more likely, this group includes some Whittingehame pupils yet to reach the school, including Kurt Tschmul.

Entertainment - Sport

The pupils at Whittingehame were often keen on both indoor and outdoor sports, ranging from chess to table tennis and athletics. 100 of them played table tennis in a league and many were especially fond of football. A football pitch had been formed near the house by locals and it was well maintained by the estate workers. A team was formed from among the keen footballing refugees and it would appear to have done very well when pitted against local boys’ teams. Whittingehame F.S. beat Pencaitland 6-0; East Linton 24 - 0 and a combined Haddington/Pencaitland team 8 - 1! They eagerly looked forward to a game against a team from Edinburgh, but history does not record that score.

…and betting!

Perhaps the betting, which became quite common at Whittingehame for a time, came from this competitive spirit. Stakes were not in cash but in the form of fruit, much prized then. The fad even led one young pupil to place a bet and to try to prove by example how far he believed the invading German troops would be able to march in a day in France, by walking the twenty-five miles into the centre of Edinburgh. He was confined to the school for a week after that for “absenting himself without permission” but was more than happy to so remain as his feet were a mess.

Other Entertainments - Music

The pupils enjoyed a wide range of entertainments and amusements separate from their domestic chores, their schoolwork and their outside labours. Music was quite important to many of them. Ivan Clarke remembers a young man called Kurt who had been a member of the Vienna Boys Choir pre-war and who was a super pianist. According to Ivan, Kurt used to play the piano to accompany silent films shown in the house. Musical evenings were a periodic feature of life and locals were often invited to come along to listen. Apart from forming their own choir, the pupils’ spirits were raised when others came to entertain. For example, the popular RAF band from RAF Drem visited to play for a whole evening, much to their and Ivan’s delight.

Musical entertainment in front of Whittingehame House. This is probably a photograph of part of the opening ceremonies in July 1939.

Farrington Drew.

Kathe Lowenthal leads a recorder quartet.

Gerd Mann,

Accordionist.

Youthful High Spirits

We can see from the following photographs that the children and young adults who spent time at Whittingehame Farm School were well able to turn their hands to entertaining themselves. The interests, youthful high spirits and questing minds of the pupils showed itself in all sorts of ways. Winter snowfalls created their usual opportunities:

Playing Chess.

A touch of the Wild West. Kurt Jahoda.

Printing the Newsletter.

Printing the Newsletter.

Archery.

Cycling. Fernande (Ferry) Engler on the bicycle

Making a Radio.

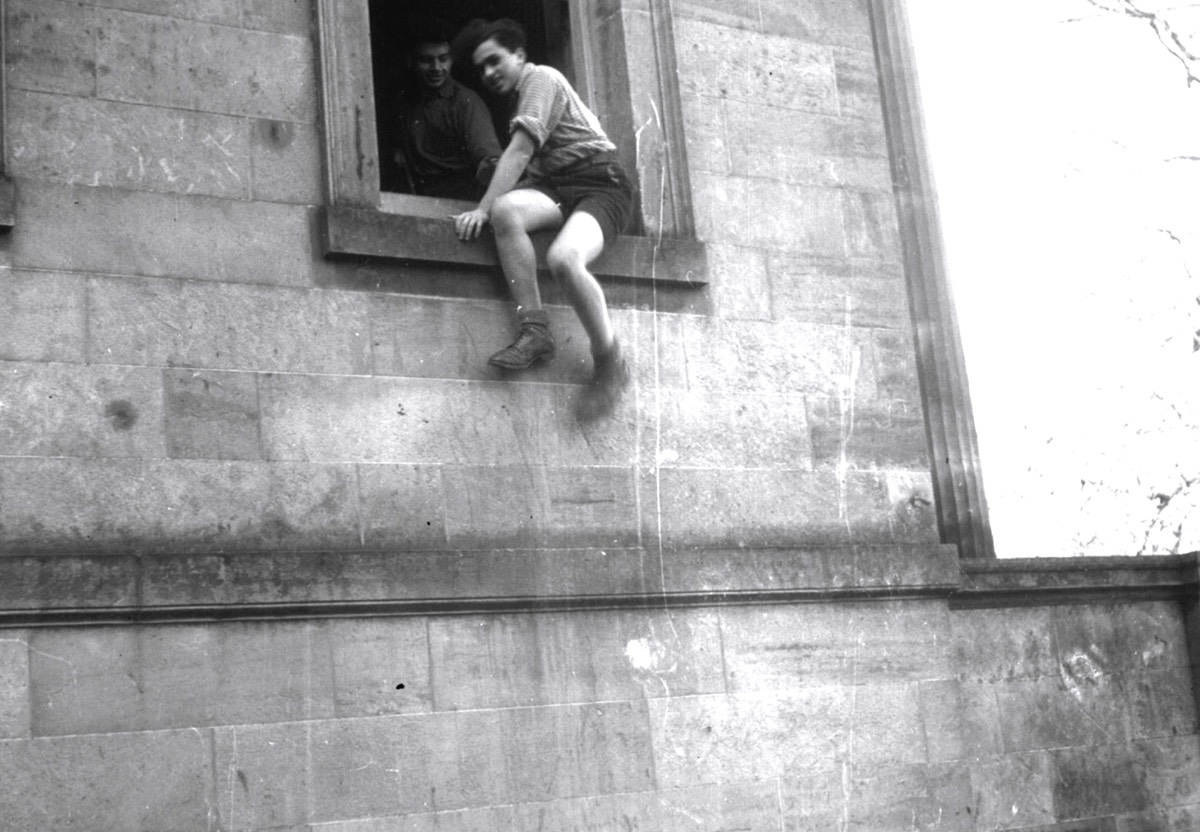

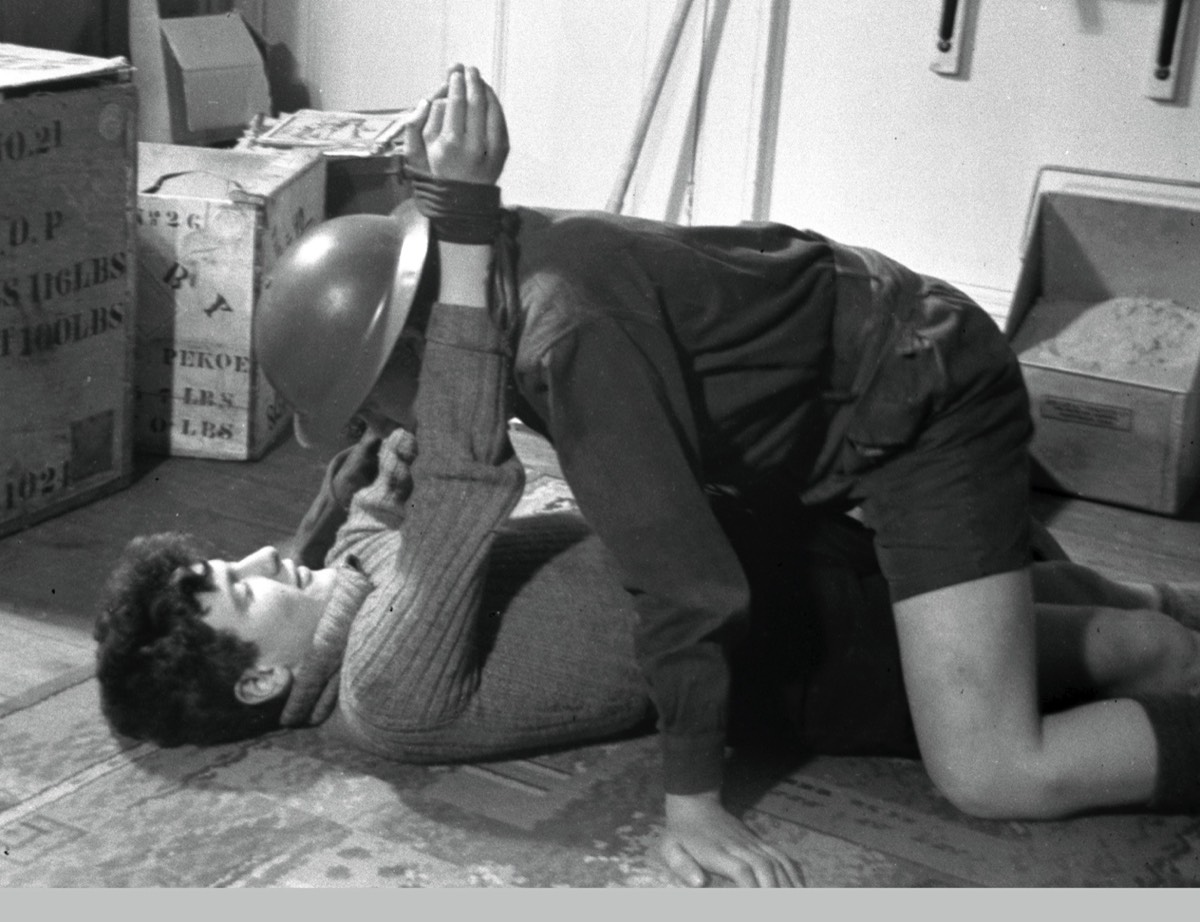

Daredevil antics.

Creating a Pipe Band.

[All Farrington Drew]

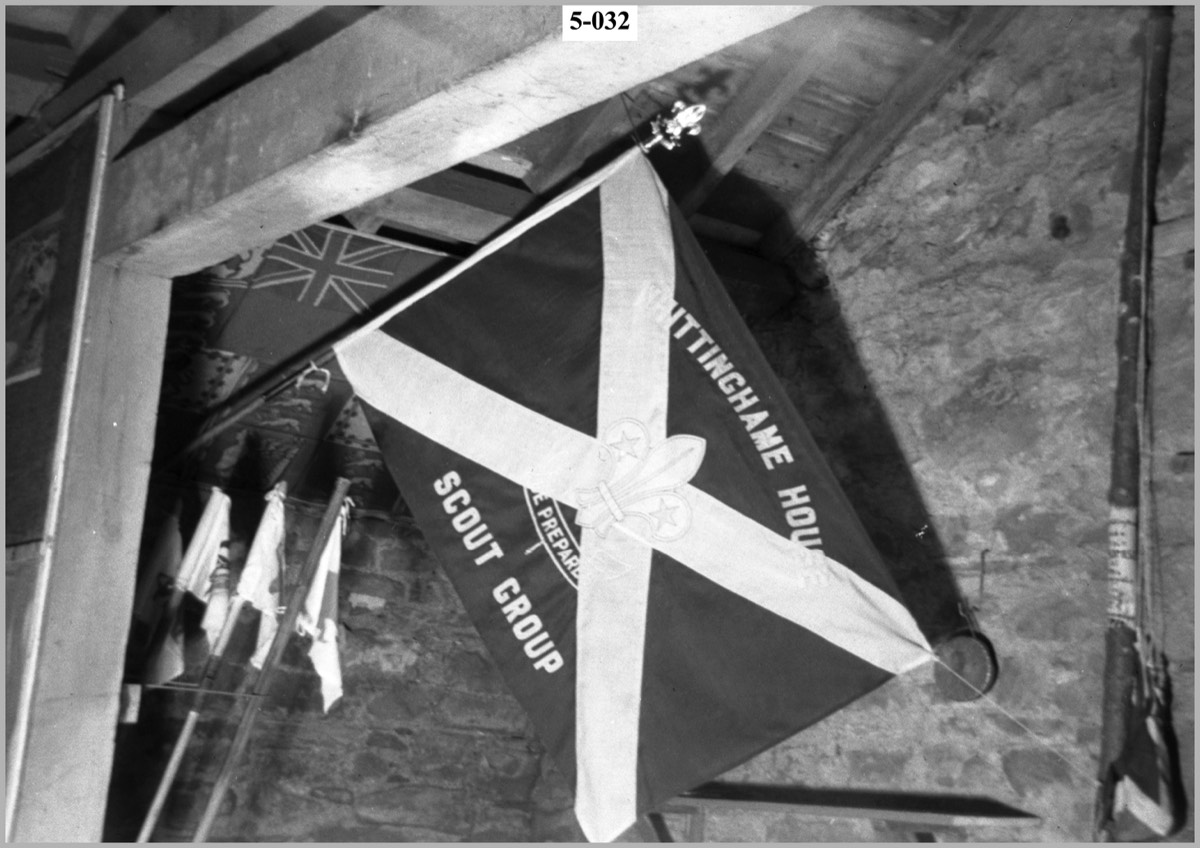

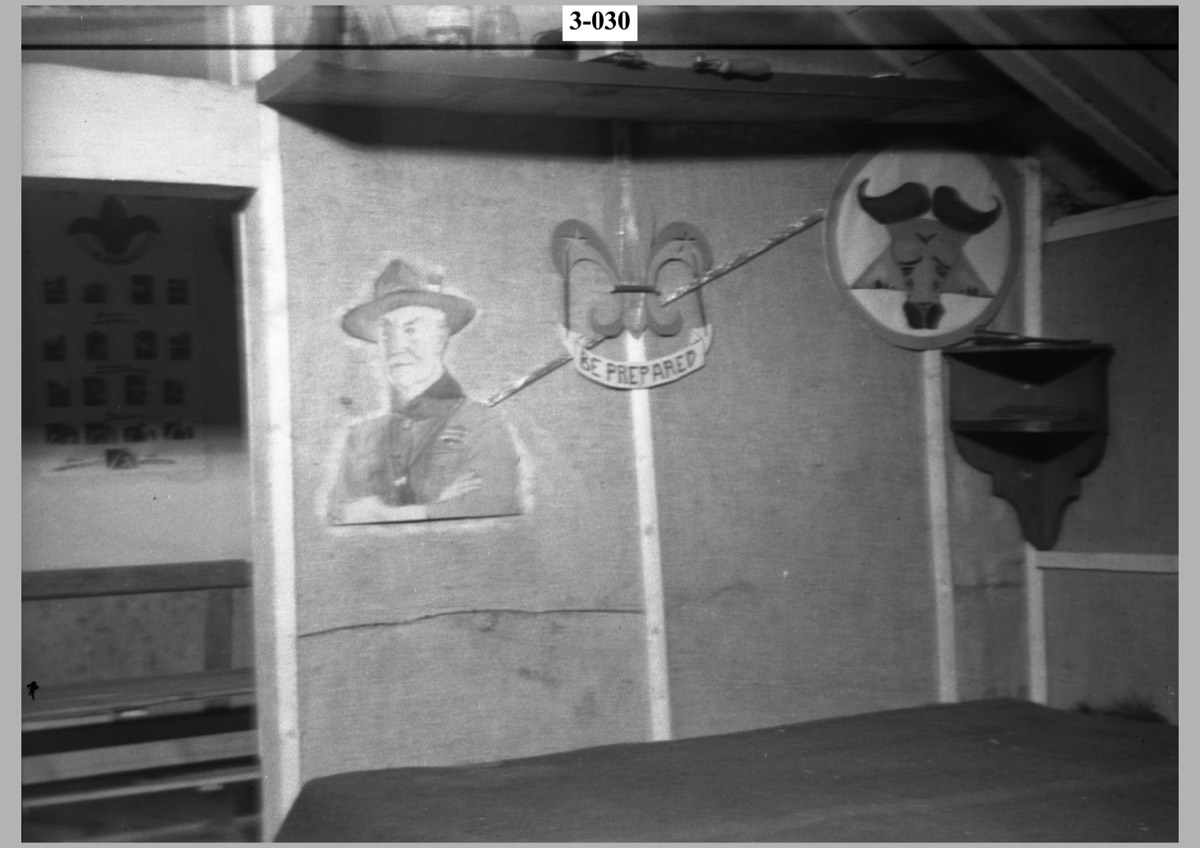

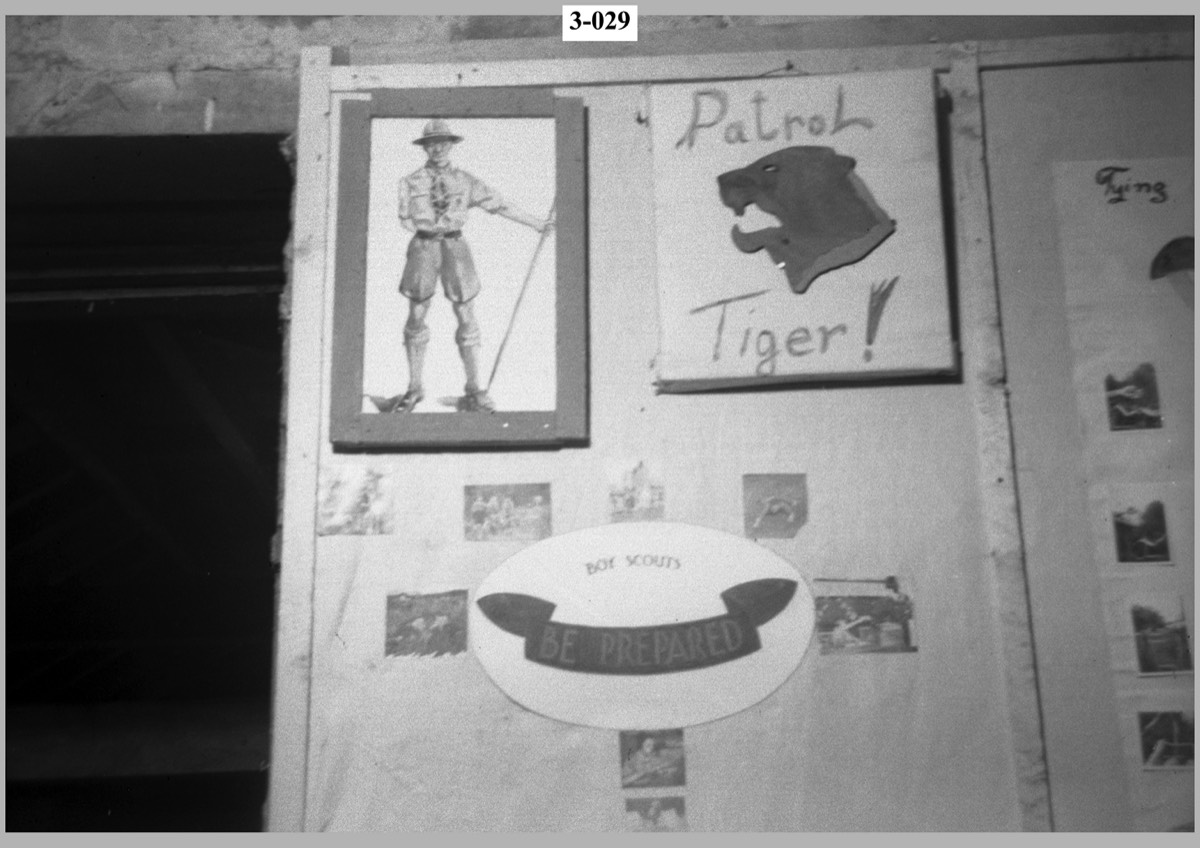

The School Scout Troop And Guide Troop

The pastimes shown above were a mix of the organised and the spontaneous. The formation of a School Scout Troop and its female equivalent, a Guide Troop, was a different kettle of fish. This required a considerable effort ranging from the provision of uniforms and flags to the conversion of a set of rooms for the troops to use. One imagines that the first two were provided by the Scout and Guide Movement, the latter by the efforts of the boys and girls themselves. How active and successful these were is unknown and hopefully someone will one day supply the answer.

The Troop's Flag.

The Scout 'Hut'.

The Scout 'Hut'.

Two Girl Guides.

An important inspection: perhaps by Lady Traprain?

ARP Duties At Whittingehame School

Nazi persecution was responsible for the enforced flight from danger of the children who ultimately found safety and peace in Whittingehame. When the war came in 1939 this danger re-asserted itself. While the school itself was never a target for the Luftwaffe, targets certainly existed in East Lothian at large and the staff, with William Farrington Drew in charge of Air Raid Precautions, was active in preparing the pupils for the eventuality and possible consequences of an air raid. That Farrington Drew took his duties seriously is evident in the photographs shown below. The pupils trained in First Aid, in the recovery of injured people, in putting out incendiaries, in the evacuation of the building and in air-raid precautions.

Sergeant Birrell from Haddington, instructs.

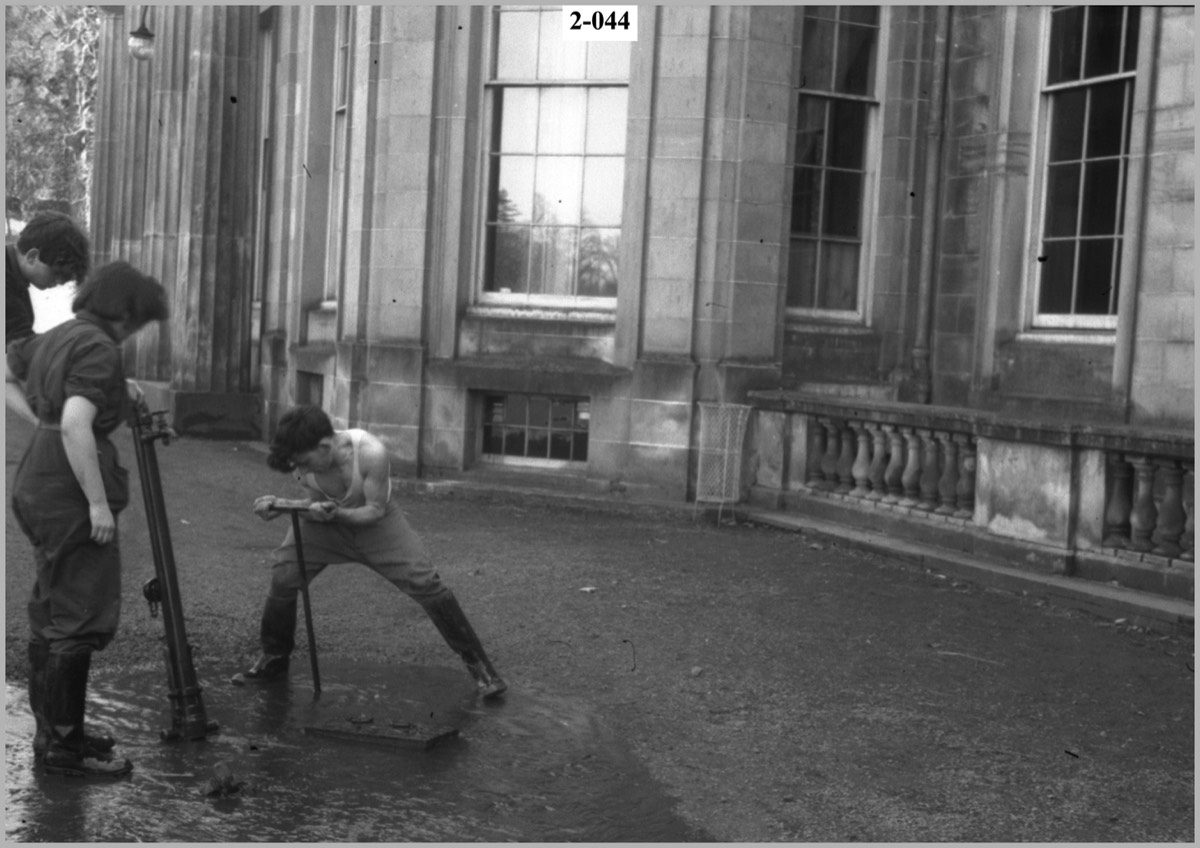

Learning to use a Stirrup Pump.

[All Farrington Drew]

Practising how to deal with an incendiary bomb.

"Tuesday afternoon brought us a demonstration of incendiary bomb control by Sergeant Birrell of the Haddington police. The Sergeant had given us a preliminary lecture in the first days of January…and he had no intention that he was just going to show us how…the boys themselves had to do the work. Well, considering that they had had only one lecture from a Scot in broad Scots…that they have only had nine months English training and in many cases only three months…the prospect of having to put out an incendiary bomb under real conditions was a trifle alarming.

The Sergeant had asked for an outside garage to be fitted up with old stuff…beds, chairs and bedding, more or less like an ordinary room…and with plenty of straw scattered around. This we did…The Sergeant came along and approved except that he did not think the whole was sufficiently inflammable…so he poured two gallons of paraffin over everything.

The first show was the extinguishing of an incendiary bomb, when the room had really got ablaze, with a stirrup pump…The boy, equipped with overalls, had to crawl in on his belly whilst those outside kept the pumps going…the Sergeant remarked as he watched the flames raging up to the ceiling…

'Go on lad…in on your belly…it's up to you now, if you want to save the garage!' and I, standing by, wondered whether the police had not rather overstepped the mark in realism. However, the lad did well and without outside aid, other than his team on the pumps, got the fire under control and extinguished the bomb. Then two different sets had to extinguish an incendiary bomb by the sand method ([using a] Redhill container) and this too they did to the satisfaction of the Sergeant."

Tragedy From The Air: 14th September, 1939

On one occasion the war did come to Whittingehame Farm School in the sad but wholly unnecessary loss of two Commonwealth pilots who crashed into the top of one of Whittingehame’s trees when they flew too low over the house and grounds. It appears they knew some of the staff or the Traprain family and had flown out from Drem to buzz the house. Unfortunately Keith Bartram Chiazzari (19) from South Africa and Alan Bishop (23) from Australia both perished in the crash. They were the first Commonwealth airmen to die in World War Two.

Eli Fachler described the crash as follows: "One of the bi-plane pilots was a friend of the Traprain, and he used to perform aerial aerobatics over the school. One sunny October morning - it was Shabbat or Yom Tov, and we were all together, just finishing our prayers - 'our pilot' hit an air pocket, one of the hazards of early aviation in hilly areas near the sea. We all rushed outside and stood helplessly by as the plane exploded on impact with the ground. We saw the pillar of smoke and watched the burning plane… We could feel the searing heat where we stood and nobody could get near to the plane to help."

It is more than likely that this is the Hawker Audax as it flies low

over Whittingehame House minutes before it crashed.

ARP Training Inside The House

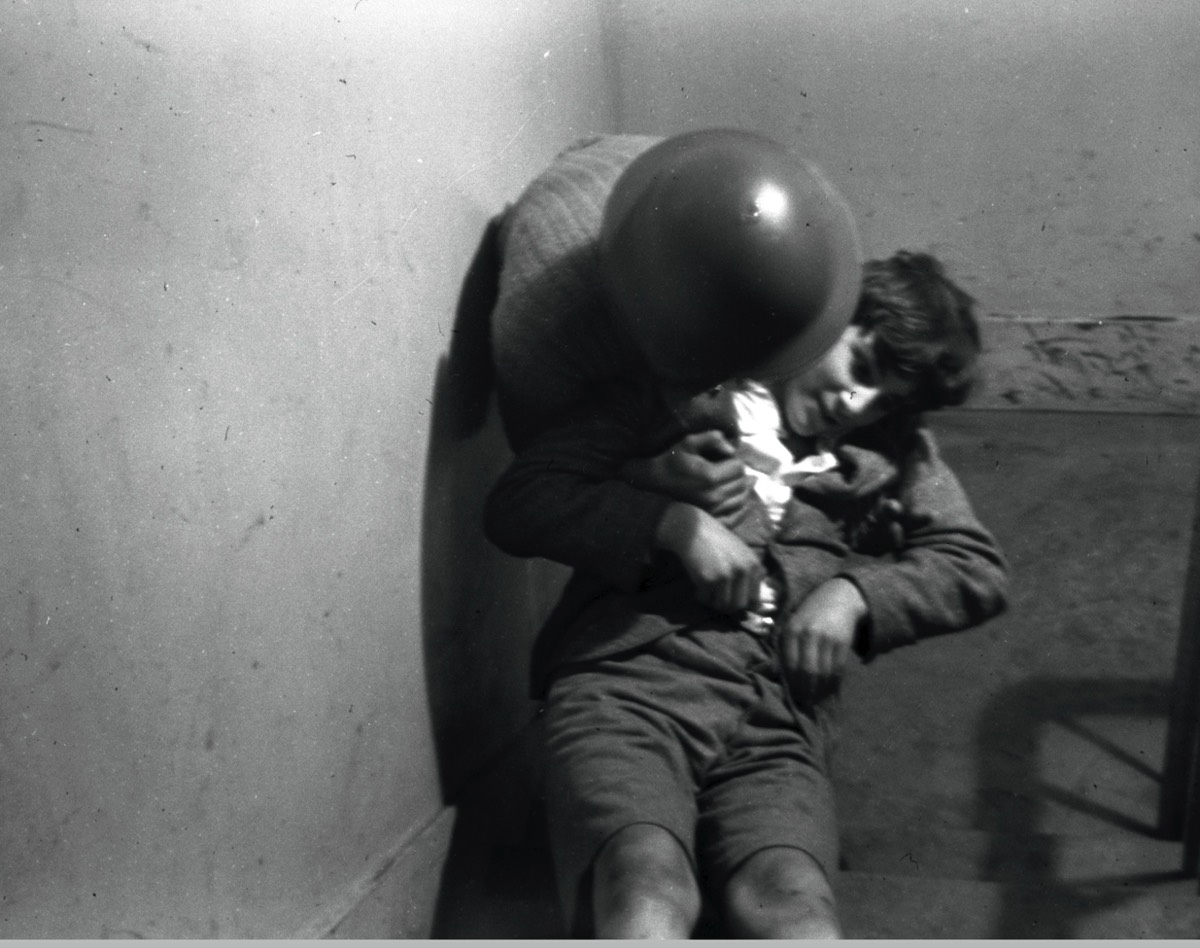

The training went on inside the house in how to evacuate the large, rambling building, how to evacuate casualties and in First Aid. It was all taken very seriously by Mr Drew. It had to be since reality was a mere bomb-aimer’s miss-directed touch away. Some of the pupils recounted their ARP experiences in a reunion publication ‘From Whittingehame 1939 to Israel 1989’. Sami Riemer remembered how it all went very wrong for him. He wrote:

"Mr Drew chose me for the key position on the ground floor where the majority of the boys lived. His own quarters were nearby and in the event of an alert I was the first to be woken up by him. My job was to rouse one designated boy in each of the dormitories on the floor. They would wake all the others in their respective rooms and make sure that everybody was evacuated downstairs in good order…Not a difficult assignment for a bright fifteen-year-old, it might be thought. But when it came to the test I failed miserably.

I simply could not be woken up! The boys told me afterwards that Mr Drew practically sat on top of me shaking me as hard as he dared to, but to no avail. Mr Drew must have been getting frantic. He had to wake up the other key personnel, on the girl's floor, in the Boys' Wing and presumably the staff too."

Learning to evacuate casualties.

Night-Time ARP Duties

A number of the pupils joined the ARP section and took their turn in night-time duties. Some did so for perceptive reasons as we shall see.

Checking the rooms

at night.

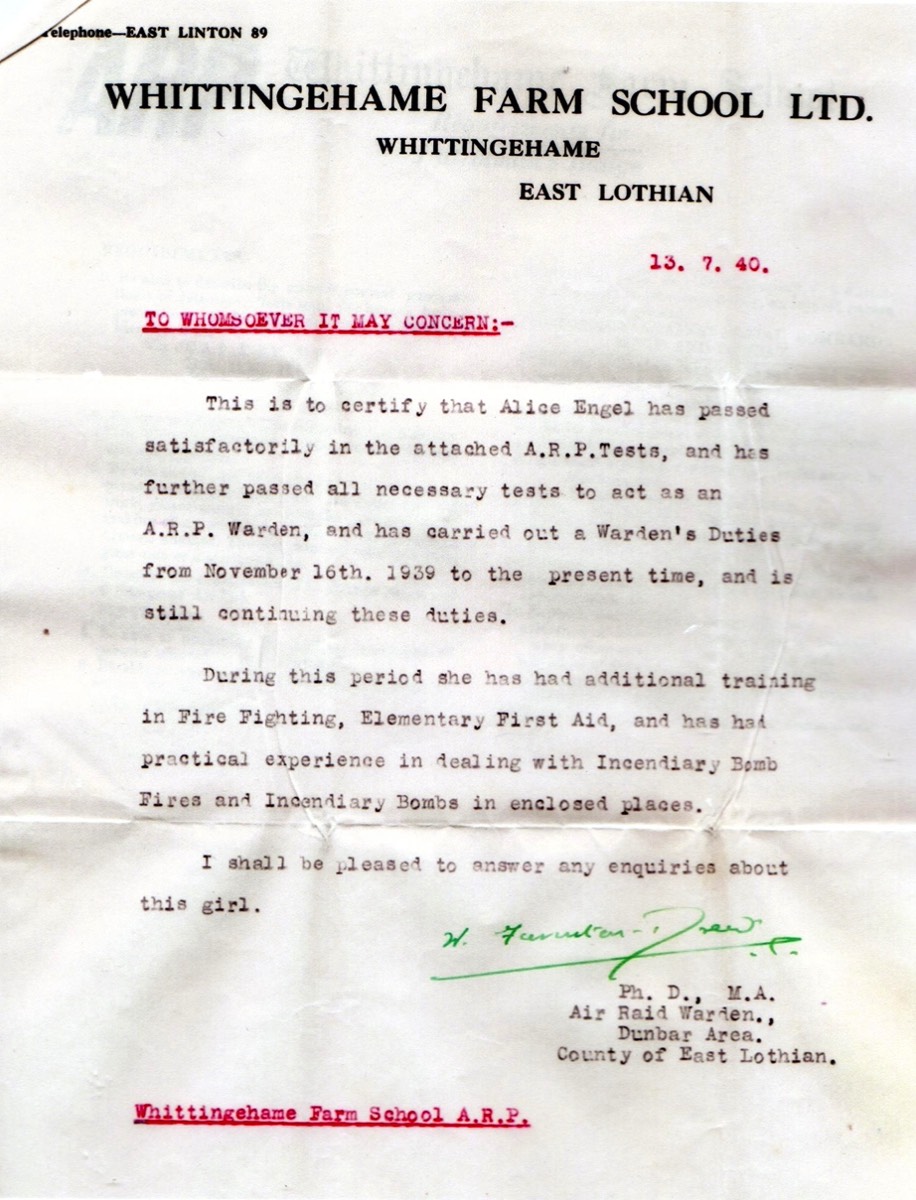

Alice Engel joined for similar reasons. She wrote: “Maybe the thing that I remember with love and affection about the war and Whittingehame is the night duty we did with the ARP. Having to do the night rounds and walking round the house when all was still, and the rest of the people were sleeping. Then we who were on duty would go outside as well to hear if there was anything going on in the sky. The most beautiful time of all was a clear winter’s night with the moon and stars so bright that one could almost read a newspaper. So cold and clear with snow underfoot and we never felt the cold. Ah, for nostalgia!”

Alice Engel’s ARP certificate, July 1940.

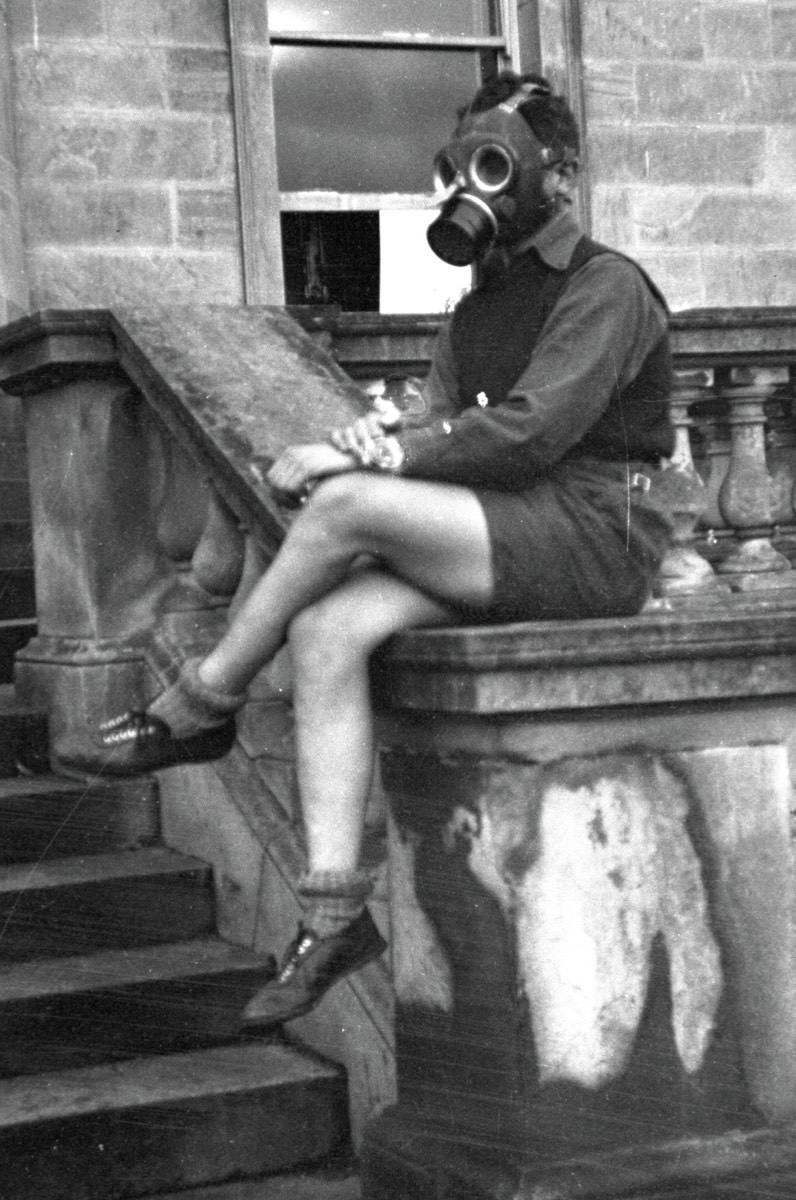

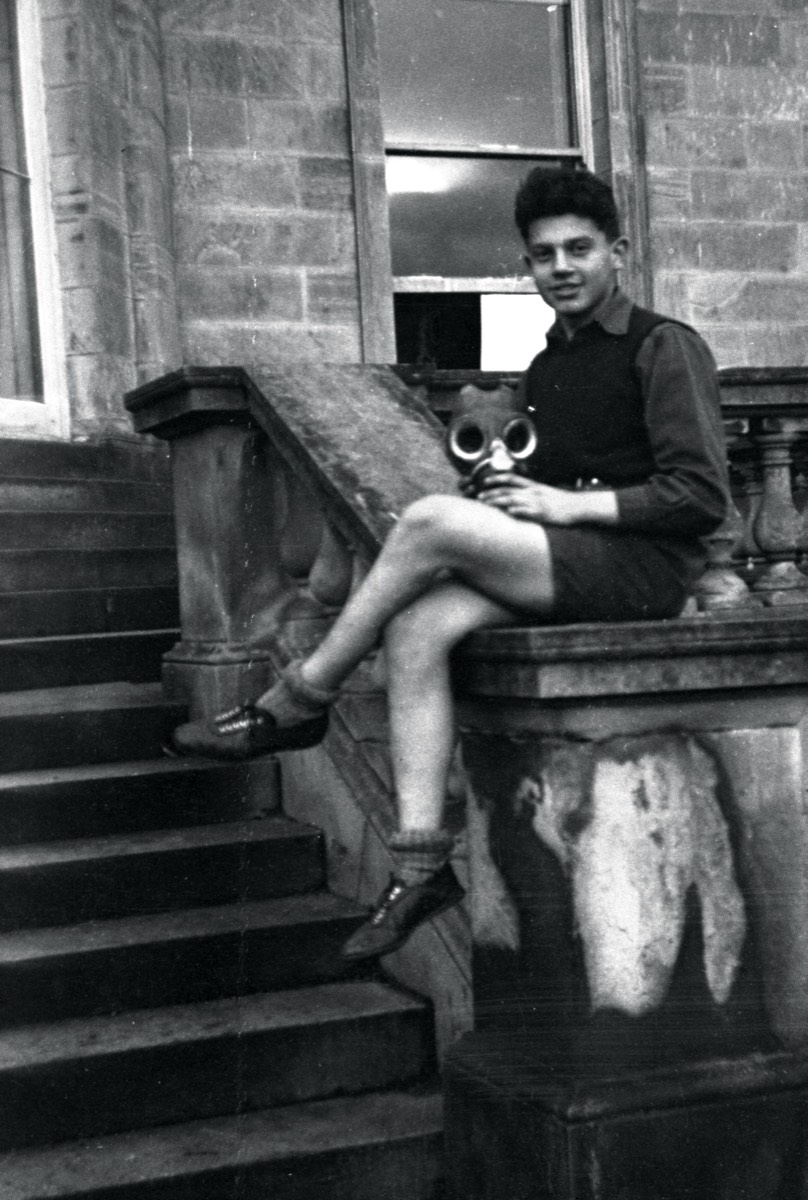

Gas Precautions And First Aid

Like all UK inhabitants, the children at Whittingehame were issued with gas masks and these, of course, had to be tried on and tested.

Anneliese Narai, a pupil at

Whittingehame from January 1939-1941

Anneliese later trained as a nurse in London

becoming a Sister in various hospitals.

[courtesy of her daughter Mary Allen]

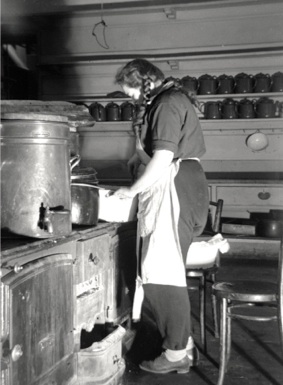

Domestic Affairs

As mentioned in Farrington Drew’s letter describing what he found when he arrived at Whittingehame, the pupils had a major role in helping to run the school’s everyday activities. An important element of this was in the purely domestic. All pupils spent many hours repairing furniture, maintaining and repairing clothing and shoes, in cleaning rooms, doing the laundry and in helping to prepare and cook the meals. Money and basic resources were short, and the pupils had to be resourceful and determined. Once again, William was ever present with his camera to record even the most mundane of activities. One gets the impression that his day wasn’t over weighted by teaching duties.

Peeling potatoes.

Slicing bread.

Cooking on the unreliable old range.

The eternal chore; washing the dishes.

At the Cobbler's last.

Woodwork; running repairs.

Sewing - The fast way.

Sewing - the slow way. Ester Golan extreme left, back.

Marie Dancygier extreme right.

Washing down the kitchen floor.

Turning off the water supply.

Shovelling off the coal from the back of the school’s own lorry, a 1930 Ford, 4 horse power, registration SS3178

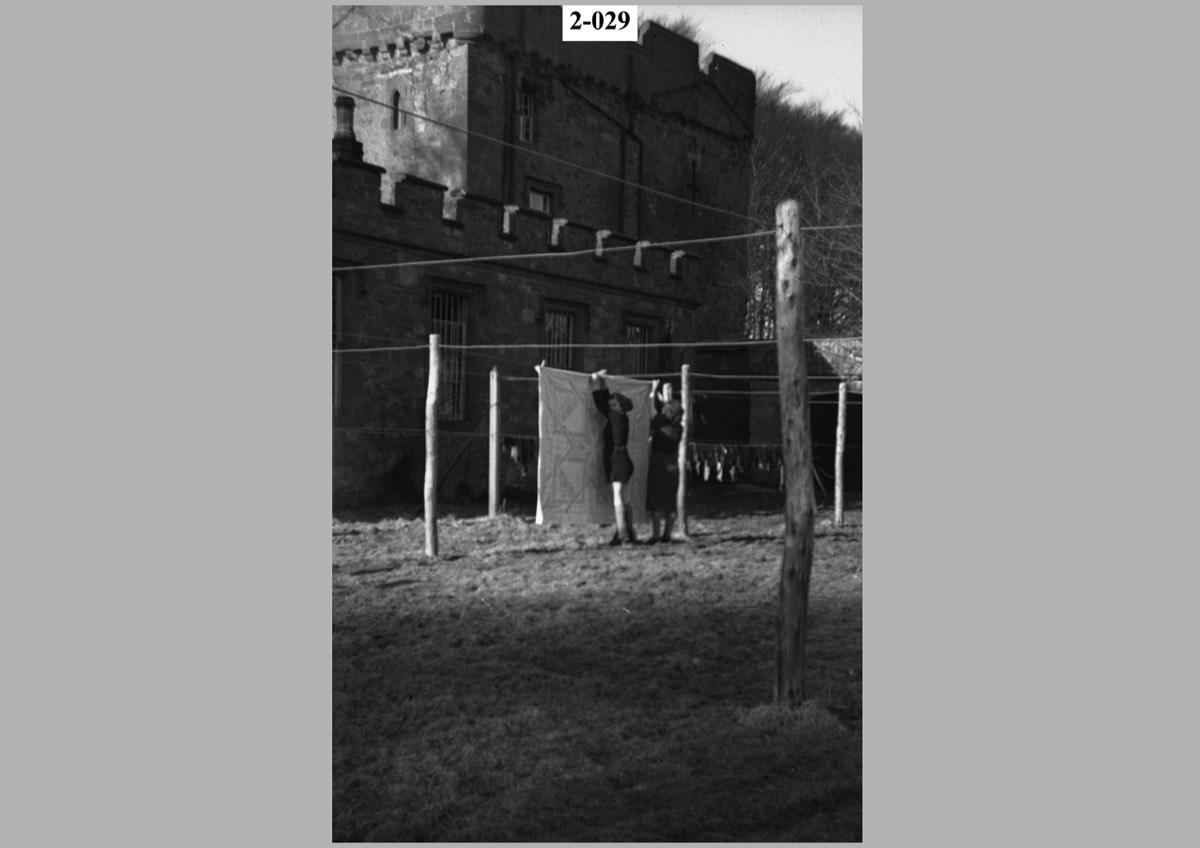

Hanging out the washing by the Tower

which was used as a laundry.

The dentist.

The barber.

Lucy Laquer - Matron

Lucy was matron to the refugee children from January 1939 until September 1941. It cannot have been the simplest of roles! Clearly, she felt she had to ‘act the part’ and could be strict when she felt discipline was required. Her image was encapsulated by one former pupil who wrote, “...it is like yesterday when we were given the ‘house rules’ by the Matron, Miss Laquer, who by the way had a heart of gold, but sometimes succeeded in hiding it.” Matron’s ‘rounds’ each weekend were thorough which required a fair amount of cleaning up on the part of the pupils. Not something they appear to have relished. Lucy wrote, “My job was to keep the house clean and tidy - no easy task. In spite of my domestic science training and my Gwerbelehrerinnen Diploma, the girls thought they knew best. They could not be convinced to sweep the stairs from top to bottom, preferring to do it the other way around!” She added the interesting comment, illuminating but very contemporary in its nature, that while “ The Sunday morning dormitory inspection was meant to help me in my work, ...I hated it: partly because I knew how superficial it was, but also because I had to trot behind the headmaster. Surely the boys should have learnt from the example of their superiors the good manners that require that a woman should enter the room first?”

Lucy wrote of her memories of Whittingehame Farm School for the reunion of former pupils in Israel in 1989. I hope they won’t mind my quoting from her account as she pulls back the blinds a little on some interesting aspects of life at the school. She confirms that the war didn’t impinge too drastically upon life at Whittingehame writing that, “They were war years, but very peaceful ones for us in Scotland. We sat out air raids in the basement of the big house. If they lasted a minute more than half an hour, all voices joined in a loud chorus of ‘chocolate biscuits, chocolate biscuits’ till the large tins were opened and their contents distributed.” Any radio sets owned by the staff had to be surrendered to Lady Balfour, though this must have been relaxed a little as the dormitories could ‘win’ the use of a radio for a week if they had been seen to have kept their room especially tidy.

Knowing that each refugee had often harrowing tales to tell, Lucy confirms that an effort was made to make them feel at home as quickly as possible. For example, new arrivals were treated to two eggs each at their first breakfast, something they greatly appreciated as they had often been on very short rations at home. Lucy was clearly much impressed by Lord and Lady Balfour’s kindnesses as she confirmed that the latter had asked for a list of the birthdays of the pupils so that she could invite them to her house on the Sunday after the birthday for a birthday meal. This treat was much appreciated by all, though one pupil caused a minor scandal by picking up the butter with his fingers! Lucy herself was frequently a guest as well.

Lady Balfour’s thoughtfulness was often of a very practical nature, as Lucy relates: “A short time after starting as acting headmistress, Lady Balfour told me she would be absent for a few hours: she wanted to discuss something with her forester. As a result of that discussion, trees were felled, the riverbed deepened and a dam built, thus creating an open-air swimming pool for our community. Needless to say, to our great delight, though not to the delight of Rabbi Daiches, who disapproved of mixed bathing.”

Lucy found kindness in other areas. She relates how: “The Edinburgh Governors were as kind as the Balfours. They often came on Sundays with lashings of ice-cream. It was ladled out by the Cohen’s chauffeur. They were altogether more generous than the London Governors. Whenever I went to Edinburgh on a shopping expedition, I was invited to a meal, either at one of their homes or in a restaurant and was never allowed to pay for myself.”

Lucy gives an interesting insight into the relative freedom of the older pupils when she described how, “Our boys found it easy to get lifts into Edinburgh, but the Edinburgh Governors did not care for them conversing loudly in German on Princes Street on Saturday morning. They were conspicuous, too, in their navy-blue uniforms. Especially their shorts, two to three inches shorter than the British norm...gave them away.”

Mention has already been made of the administration of the school, of how the pupils shared a not inconsiderable portion of the responsibility of the organisation of everyday life there. Lucy’s following description casts further light on this aspect of life at Whittingehame Farm School. She wrote:

"When we had been at Whittingehame about six months, the Headmaster, Mr Maxwell, decreed that no more German should be spoken in the Sichoth, the lengthy council where all the matters considered important to the community were discussed and argued. Instead the members could choose between Ivrith and English. To spite the Head, they spoke Ivrith, haltingly and by no means faultlessly. The Sichoth were always attended by Mr Maxwell and occasionally by Lord and Lady Balfour. They sat behind the Hebrew masters, who had to translate over their shoulders what was said: not too difficult a task, since it contained lots of 'ums' and 'ers'. At the end of one speech the Headmaster said: 'I quite understand what you were trying to say, Kurt, though your Ivrith is not quite the same as what we speak here in Scotland.'"

Food

The subject of food comes up a number of times in the evidence, as one might expect it to among a community of growing bodies. It appears that crises in that department were not uncommon, partly because of wartime shortages and cost pressures but also because of the somewhat unreliable stove upon which the cooking was done. Lucy Laquer had a terse comment to relate as regards the latter. She wrote: “The kitchen range (model 1839!) donated by the factory that manufactured it, was a vast expanse of iron, and by no means easy to master. A previous cook had pronounced on it in unadulterated Berlin dialect: ‘Der Herd jehort jut jeputzt und weggeschmissen!’ [The range should be well scrubbed and chucked out!]” She also enlarged upon the cost of feeding the children when she wrote: “Things were cheaper in those pre-inflationary days. I bought a stone of apples from the estate for a shilling - but it was no easy task to feed 160 people on the tight budget of seven shillings and sixpence per person per week.”

William Farrington Drew was moved to write to the Edinburgh Governors about the quality of the food at Whittingehame and commented upon the reaction in a letter to his parents. He wrote: “I think I have not told you of the visit of Mrs Weizmann nor of May Mundy, our Secretary, who visited us in answer to my letter of complaint about the food. May is fat, wadgy and gushing and a vegetarian, so she was about the last person who was suitable to make an inspection of the food. She always has special meatless dishes prepared for her in the kitchen and says, ‘Your matron spoils me, ha-ha-ha.’ And we grimly join in her little giggle which ends most sentences.”

Lunchtime: the quality of the food may have fallen below acceptable standards on occasions but clearly we can see

from these photographs that the quantities provided were substantial.

Internment

In 1940, with the Phoney War a recent thing of the past and the threat of invasion a reality, the older pupils at the school, along with some of the German or Austrian born members of staff, were unexpectedly faced with a dramatic change in their fortunes. They were arrested and interned as enemy aliens. Erich Yitzchak remembered this unpleasant experience and wrote about it in the booklet, “From Whittingehame 1939 to Israel 1989”. He wrote:

"We were a group of thirty-six representing all the various groupings within the school. Accompanied by British guards, we travelled south to Lingfield Race Course, which had been turned into a PoW camp for German sailors caught in British ports with the outbreak of the war. Nearly 500 inhabited the camp and it came as a shock to us to be crowded into those same quarters and dining hall with German Nazis.

They were practically 'ruling' the camp and the guards felt afraid of them because of their disciplined Nazi organisation as well as of the possible dangers of an invasion. We, the Whittingehame group, had to decide how to handle such a confrontation, which the British had at the very best not understood.

After being served food by the Germans, we decided unanimously to go on hunger strike. …The British could not understand the mess they had made until they were told that we [were] demanding our own kitchen with kosher food and a reliable cook to dish out such food. After one whole day a French Jewish cook arrived…

The next morning we went out for roll-call… After the Germans finished their eins, zwei, drei, etc., we counted in Hebrew with the last chaver translating into English. The British were flabbergasted and Hans Heinemann had to explain that we were Zionists, our old/new homeland was in Palestine and our language Hebrew. We had a hard time until the Germans were sent to Canada and I remember a number of confrontations.

Some evenings we used to sit on the race-court steps and sing. The Nazis sang their antisemitic and Nazi songs. We in turn spontaneously sang Socialist or our Hebrew ones... [Once the Germans left] we passed the time with Italian PoWs who were civilians and only in part Fascists.

It may be important to remind ourselves that even amongst the Germans there were some anti-Nazis - some twenty men, two of [whom] were beaten up by the Nazis because they dared to contact us. After the Italians left, the camp turned into a large Refugee Internment camp and the cultural side of life became enriched by lots of talented people.

By mid-August the Home Secretary, Herbert Morrison, had been forced to release us as friendly aliens, but until the end of the war we had to report to local constables, even for a twenty-four hour absence. We returned to Whittingehame Farm School stronger in our beliefs…"

No doubt the return of the internees was a joyful occasion for all concerned. One can imagine, however, that this recent experience, combined with the determined streak exhibited throughout by the group of ex-internees, must have made Charles Maxwell and Lucy Laquer’s jobs that much more complex, if not difficult. It is no wonder that Mr Maxwell determined to run the school along lines which imitated a kibbutz rather than along the lines of a boarding school, already attempted so dramatically unsuccessfully, by the first Headmaster.

After Whittingehame

Once pupils reached their seventeenth birthday they had to leave Whittingehame and make their own way in life. That was an important element of the conditions the British Government had set before it would agree to the Kindertransport refugee resettlement programme. The Government initially had not intended that the Jewish children would remain in the UK on a permanent basis (though many eventually did). Some found jobs and settled in the UK, others set about the difficult task of trying to get to Israel, others moved on to the USA and elsewhere. For many, of course, there was still a war to win and a number of former Whittingehame pupils joined the British Forces. Haim Shoked (Kurt Tschmul) joined the British Navy (as recounted below).

Learning more about Whittingehame Farm School

A contact with the Jewish community in Dublin led to my giving a lecture via Zoom to the Irish Jewish Forum in 2021. Again, a new contact was made, this time with the son of Eli Fachler, another former Whittingehame pupil. Yanky has been most generous in supplying a host of new information about his father and his time at the Farm School. I am hugely indebted to all of these generous people who have helped to expand our understanding of what happened at this most unusual refugee centre.

What now follows are the accounts of former pupils at Whittingehame. They are given at length because each account not only features the personal experiences of a refugee but their accounts also reveal significant snippets of information about life at Whittingehame. They are included in the order Jack or I obtained them.

1. Laura Samuel

2. Harry Nomburg

3. Ester Golan

4. Kurt Tschmul

5. Norbert Abeles

6. Eli Fachler

If you can add to the Whittingehame Farm School story, please do.

1. Laura Samuel

Laura (right) and her brother.

Laura Samuel (Lorchen Buchsbaum) revisiting Whittingehame House.

Laura revisited Whittingehame when she was eighty-three in 2007 and wrote the following of life there. She described her time at Whittingehame as the happiest of her early life and she was only sorry that it didn’t last longer. She said, “The only things that were bad about our stay at Whittingehame were that we were not paid when we worked in the fields or on the estate and that we had to leave at sixteen to go out into the world on our own, without a good education and with poor English. We worked for half the day and attended school for the other half. Some worked in the fields and some on the estate without pay but in lieu of our board and lodgings. Our headmaster, Mr Maxwell...did not interfere with us and we ran the school like a kibbutz. We set up a committee which made all the decisions and wrote the weekly work schedule with Mr Maxwell’s approval. We all spoke German since there was a mixture of Austrians, Czechoslovakians, Poles and Germans.”

“I came with the Kindertransport but not with the group as I was not allowed to travel with them because of my passport being Polish. I had one other travel companion and we left Berlin for Hamburg where we were met. There we were put on a ship to Leith in Scotland and there we were met and taken to Whittingehame. I was happy to leave Germany but very upset to leave my parents. My brother came three months later but by a different route.

In Whittingehame we were around 180 from different countries (Czechoslovakia, Austria, Poland, Germany) all speaking different languages, but we all learnt to speak German. Our so-called teachers were a mixed bunch: one from Israel, two from Germany and two from England. It was called a Farm School but wasn’t run like one. We had half a day’s schooling and half a day’s work. We did all our own housework like cooking, cleaning, washing clothes and dishes, setting tables, etc. We had two dining rooms, one for the very orthodox (because of prayers before and after meals) and one for the non-religious. The ex-ballroom was made into a Synagogue, but we had no Rabbi and we did it all ourselves.

The work schedule was worked out by a committee of our own: I mean the rota. Our headmaster was English (sic) but let us do it all our own way and it worked beautifully. So did the teachers who did not teach much as I learned nothing, but they were there officially only so that it could be described as a school. We had self-discipline and no-one tried to get out of doing what they were supposed to do. Half of us worked on the farms for the Scottish farmers as Land Girls and Boys.

Nearly all of us and I say almost all except for a few, found it was the best and happiest time when we came. We were luckier than most others who went to families. We all had permits to go to Israel after two years, but war broke out and only twenty-five managed to go and the rest of us got permission to stay. We dispersed to go all over the world and not all went to Israel. As far as I know all ended up one way or another as good, honest and successful in life even if not many were rich. A few managed to get degrees and became doctors, professors, businesspeople.”

Left - Laura with Jack Tully Jackson and - right- standing beside a model of Whittingehame House.

Courtesy of Bill Rarity.

2. Harry Nomburg

Harry Nomburg (alias Harry Drew)

Harry Nomburg was another Whittingehame boy who joined the British Forces, in his case, the army and later the Commandos. In this photograph Harry is kneeling bottom right. Harry joined a rather special unit, 3 Troop, 10 Commando, made up of Jewish refugees who all spoke German. To hide their origin, each adopted an British surname. In Harry’s case he adopted the surname, Drew, in honour of William Farrington Drew, his former teacher at Whittingehame. You can find Harry’s story in the section under Fighting Back - Personal Histories. Here Harry tells the story of his part in the landings when he went ashore with Lord Lovat’s 1st Special Services Brigade on D-Day itself. Harry emigrated to America in 1948 and joined the 82nd Airborne Division of the American Army. He died in New York on February 21st, 1997. Engraved on his tombstone is;

“Fearless of those he fought

D-Day, Normandy

Selfless to those he loved

Family and friends”

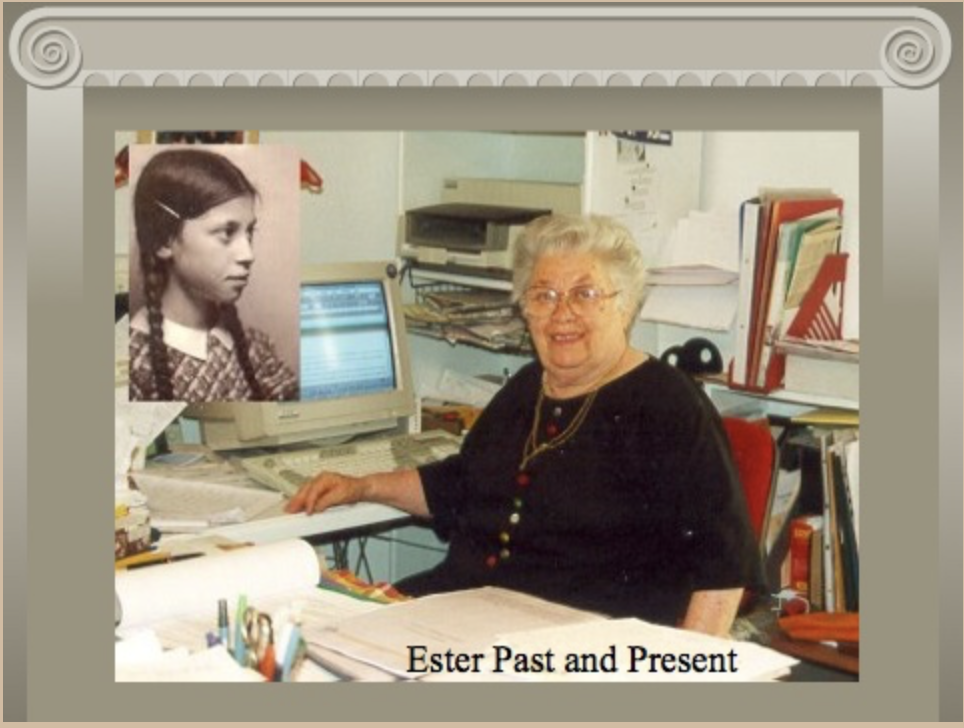

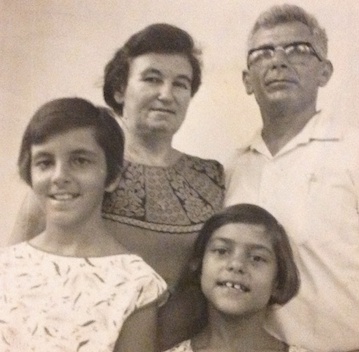

3. Ursula Dobkowsky's story - (Ester Golan)

Ursula Dobkowski on a visit back to Whittingehame

after she’d left to act as a children’s nurse/home help

Ursula Dobkowsky (Ursula Brodsky - Ester Golan) remembers what it was like to be a Jew in Nazi controlled Germany and how she came to Whittingehame

Ursula came direct from Berlin to Whittingehame with the first group to leave under the auspices of Youth-Aliya, with Palestine-Amt as guarantors. Ursula’s mother Else, living in the family home in Glogau, Germany, was a founder member of the Zionist organisation in the town and emigrating to Palestine was a dearly held ambition for the whole family. The family which lived well and ran a flourishing wholesale leather dealership and shoe shop in Glogau, suffered financial ruin due to the ramifications of the Wall Street Crash in 1929 but had recovered considerably by 1931. Ursula’s story, which follows, illustrates the growing desperation of Jewish families who wanted to emigrate to Palestine or elsewhere as the Nazi movement tightened its hold on German life and state. Ursula father Arno had fought in the German Army in World War One and she had an elder brother, Peter, and a younger sister, Marianne Renate. Let Ursula now take up the story in 1932:

At School

"Peter, after 4th grade, in 1932, was enrolled in the Catholic Gymnasium. As a son of a war veteran with the Iron Cross he got a stipendum. The curriculum included Latin, Greek, English, French and many Classical subjects. When it came to Ursula’s turn, Jewish children were no longer admitted to the Gymnasium or Lyseum. While all the better pupils moved on, she had to stay on at the elementary school. The curriculum was basic at best and was changed to include a lot of Nazi propaganda. Ursula was the only Jewish girl in her class. Nobody talked to her and during the break, while other played together, she stood all by herself in the corner of the schoolyard.

In spite of all the injunctions against Jews, she participated in the ongoing activities, like drawing the Rathaussturm, family history research and learning to swim. In the summer of 1936, the teacher insisted that it was part of the curriculum, even if at the entrance there was a big sign ‘Fuer Hunder und Juden eintritt verboten’ (entrance forbidden for dogs and Jews). In those early days in the early 30s, boys joined the Hitlerjugend and the girls the BDM (the Bund deutscher Maedchen). In Glogau the Zionist youth movement was the one most Jewish children turned to. The Jewish community increased its activities, especially those for children, with Else Dobkowsky often giving a helping hand with costumes and makeup. Else also helped to set up a Zionist youth movement, which Peter and Ursula joined already in 1932. When Giora Josefsthal (who years later became a member of the Knesset...) heard that there was only Makkabi in Glogau, he made all the arrangements for the entire group to switch over to Habonim, a pioneer-oriented movement, directing its members to Kibbutzim....

Trying To Emigrate

Arno, being Jewish, could not find any employment at all. Else took on an Eduscho agency, taking in orders from Jewish families for coffee, tea, cocoa and chocolate. Being an excellent housekeeper and cook, to earn a bit of extra money, she did catering for birthdays, Bar-Mitzvah or other celebrations. ...Times were very difficult. Else and Arno were desperate. All efforts to find a way for all of the family to emigrate came to nothing. They heard of the possibility for children to be adopted in America. They filled out a form for Ursula and sent in a photo, one of those quick, cheap ones. It was returned with the remark that nobody would want to adopt such an ugly girl. Maybe if Ursula had had her hair done up nicely, a good photographer could have made something of her. But that did not help either. Meanwhile life went on, such as the outings with the youth movement. Ursula, being the smallest, had a hard time keeping up with everybody, but she did. She came to bid farewell to the first family that left Glogau in 1935 for Erez, Israel, and wished she could go along with them.

In 1936 her brother left home with a backpack and water bottle to go to a special Aliyah school in Berlin in preparation for joining Youth Aliyah. Else bid her son farewell ...

Moving To Berlin

The following year Ursula, dressed just like her brother, went off to a Habonim summer camp in Blankenese by Hamburgh, at a farm belonging to the Warburg family. There was a constant increase in restrictions for Jews and life in Glogau became more and more unbearable with no means to support the family. In 1937 Else went to Berlin to look for a small flat and a job. She found employment, as a household help, with Mrs Guttman and Mrs Wertheim, head of the Jewish-women organisation. Packing up to move to a much smaller place meant reducing the household and leaving behind belongings, such as furniture, curtains, books, paintings, toys, but above all parting from the extended family, old acquaintances and friends.

In December 1937 the family moved to a two-roomed flat in Berlin. No sooner had they got there, than they were told to move out again: Jews were not wanted there. They felt very lucky to find a place in Courbiere Str. 16, its entrance through the back yard. It was near Wittenberg Platz and Kurfuersten Strasse, close to the Jewish Cultural Club. Ursula was placed, for the remaining part of the 8th grade till Easter 1938, in a Jewish school in Klopstock Str. She did not know a soul in Berlin. She had a hard time catching up with the main subjects, Hebrew and Jewish history, never having studied them before in the Christian school.

Else’s Mother Leaves For Portugal

It was hard to get to make new friends, as there was constant moving, families emigrating, new ones moving to Berlin hoping to find a way out. Not knowing a soul in her vicinity Ursula was left to herself most of the time. For a few months she enrolled in an additional grade class, which was geared to keep the children who had finished their elementary education, off the street. Emil Oppenheim [an uncle] managed to get permission from the Portuguese government to let his mother Bertha Oppenheim [Else’s mother] join him in Oporto. On the 29th of January 1939, Else brought her mother, who had always lived with her, to Hamburg to see her get on board a freighter leaving for Lisbon where Emil would pick her up. For Else, never to see her mother again, was a hard blow.

Else had left no stone unturned in her efforts to get to Palestine. In September they invested their last pennies to be able to join a group leaving via Antwerp... travelling via Trieste and Istanbul to reach Palestine. But there was a long waiting list. Meanwhile Ursula hoped to fulfil her ardent wish which was to follow in her brother Peter’s footsteps and go with Youth Aliyah to a Kibbutz...

Kristallnacht

In October 1938 Ursula was finally accepted to join a preparation camp, taking place at the estate of the Schocken family in Ruednitz, near Berlin. There were some forty children aged around fifteen to be engaged in agricultural work for a month to prove their capability for Kibbutz life in Erez Israel. The 10th of November 1938, abruptly interrupted work on the farm, as well as all cultural and learning activities. Locked up in a room without radio, telephone or a newspaper for a couple of days, they had no clue as to why or what it was all about. Even when they had returned to the regular work schedule, they had heard rumours and were deep in contemplation, but never guessed as to the vast changes that they were to encounter on their return home. The preparation period was over by the end of November 1938. A panel had to approve everyone individually and the attending doctor turned Ursula down because of her being underweight for her age. This was a bitter pill for her to swallow. She feared that her parents would leave via Antwerp and she would be left behind... Much later she found out that the allocation had been cut in half and that those over sixteen years of age who were in danger of being sent to a KZ, a concentration camp, were given priority.

Synagogues had been burnt down and Jewish schools were closed. A waiting period set in, hanging on and hoping something would turn up. Ursula’s carefree early childhood had come to an abrupt end.

Kindertransport

Trudi Wiessmueller, a Christian woman from Holland, had been to see Eichmann in Vienna and had got permission for children up to the age of fifteen to leave, unaccompanied by grownups. On December the 2nd, 1939, in the first Kindertransport, 500 children, some of them mere babies, left for England. They were temporarily housed in a summer camp in Devonport ... For each child a guarantor had to be found before more children could come. Foster homes, big houses or hostels had to be found to accommodate these children. Else was worried especially about what would become of her daughters. Recha Freier was trying to find placements for thirteen to fifteen-year olds in Holland, Sweden or England, at least until certificates could be got for them to join Youth Aliyah at a later date. ...Else consulted with Recha, who promised to see whether she could get Ursula onto one of the lists to go to England.

With no news, every day seemed like a year. Else, ever hopeful, carried on with her preparations in getting everything together to pack, in case there would be an opportunity, either for all of them or at least for the girls to leave. Lists were made to decide what to take, what to leave behind, what would fit into just one suitcase and a backpack, nametags had to be sewn onto every single item and some clothes needed alterations. At least it gave Ursula something to do. Else, almost daily, went to the Jewish authorities to plead with them. Betty-Hope, Arno’s sister on her way to America had stopped over in England and had found a family in London that was willing to take in little nine-year-old Marianne-Renate. Ursula was promised a place on the waiting list of a Kindertransport for the older children, perhaps under the auspices of Youth-Aliyah.

Ursula Leaves Her Parents And Germany

On the last day of Pesach, the call came to report at 10 o’clock in the evening to the Anhalter Bahnhof [Station]. A small transport of fifteen children was leaving for Whittingehame estate, the home of Lord Balfour in Scotland, via Flissingen in Holland, Dover, London and on to Edinburgh. The parting words ‘lehitraoth bearzenu’, till we meet again in our homeland, drone in Ursula’s ear up to this day. There was no time for tears. The train rolled in, last checkups and within ten minutes waving hands receded into the background.

[Ursula noted the parting words of her parents. These were ‘Do not be tempted by bad fellows Proverbs 1/10’ - her father. ‘As long as there is a future there is hope. Proverbs 23/18. See you again in our homeland - her mother]

The train stopped at the German/Dutch border. Everybody was ordered out for passport and luggage inspection. Only half the group had been dealt with and were told to get back to their compartment, when all of a sudden, the train left the station. Their luggage and passports stayed behind. Fear grabbed Ursula. Would the Dutch border police send them back to Germany? They were used to such incidents and told the frightened little girls not to worry and stay on the train to Vlissingen and to wait for the next train, which would bring the rest of the group. Ursula managed to phone Gisela Warburg in Berlin who was working for Youth Aliyah to inform her and ask for advice. Soon a couple of Dutch ladies from the Jewish community turned up and took care of rebooking the boat that had been missed.

The Channel crossing was rough and exhausted they reached Dover and then went on by train to London. They changed station and went on to Edinburgh and from there by bus to Whittingehame...Lord Traprain had put it at the disposal of Youth Aliyah for housing Jewish refugees and a farm school had been established.”

Ursula on the right at Whittingehame Farm School.

"…you are lucky to have all your children with you. We on the other hand are poor and abandoned parents. All our children are scattered far apart all over the world. I have given up all hope ever to be able to see them again. That is bitter. Even all the love that is shown to me by my dear husband, by my colleagues and friends can't help me to get over that. Nobody, but nobody, can imagine how I long to be with my children. I simply have to bear up to it. That is hard but I try to carry that burden in dignity. I do not complain about it to a soul. Words of sympathy do not help at all…"

Ursula’s parents were sent to Therenienstadt in October 1942 where Arno was killed on the 10th of February 1943. Else was taken to Auschwitz and was gassed in July 1944.

Whittingehame Farm School

"With no memory of the last part of the trip, Ursula had arrived in a new and strange world to her, six beds on either side of the room, an orange box between them and twelve unknown faces. She sat on her bed, her arms slung around the rucksack, which was too big to fit between the beds. 180 refugee children, aged thirteen to fifteen, from Austria, Czechoslovakia, Danzig and all parts of Germany thrown together, having to take care of themselves and look after the farmland. Most of the children were members of Zionist youth movements, Habonim, Shomer Hazair and Bachad, with the intention of reaching Palestine as soon as possible.”

Ester. Past and present.

Looking back on her years in the UK Ester wrote: “We did not suffer loss of identity as many of the other refugee children did. I managed to remain true to my people which was especially difficult once I had to leave Whittingehame and stand on my own two feet in a strange world. Whittingehame became home away from home for most of us. While there I felt relatively secure. Of the six years I remained forcedly in Great Britain, those days were the happiest of them all.”

Ester died in 2013 in Jerusalem.

[Editor: I am greatly indebted to Ester’s son, Dan Golan, for his kind permission allowing me to quote at length from Ester’s writings.]

4. Kurt Tschmul's story

Kurt serving on a frigate

in the Royal Navy.

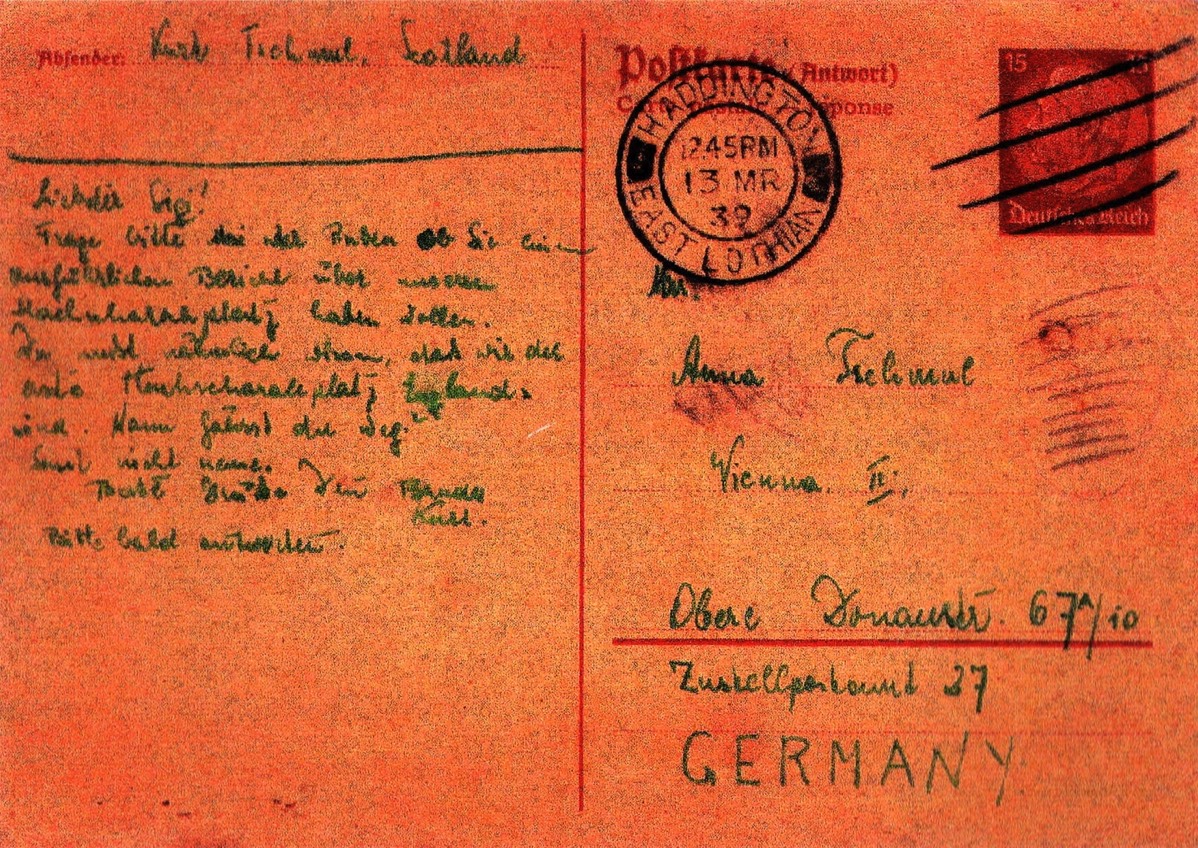

This card was sent by Kurt to his mother to tell her of his safe arrival in Scotland.

Kurt Tschmul (also known as Haim Shoked), Another Former Pupil.

His daughter, Dr Ruth Amir, remembers him:

“My father, Kurst Tschmul, one of Balfour’s bairns, was born in Vienna in July 1922. He passed away on the same day in 1979, in Israel. He was only sixteen when the political union of Nazi Germany and Austria came into effect in March 1938. Following the ‘Night of the broken glass’ later that year, his father was arrested by the Nazis and sent to a concentration camp. He was released later and was ordered to leave Austria immediately. My grandparents had sought to increase the odds of survival by sending each of their two boys off to a different refuge. My father was sent to Britain on one of the first Kindertransports from Vienna in December 1938 and [soon came] to Whittingehame Estate. His younger brother went on a Kindertransport to Sweden a few months later, while his parents managed to flee in the last ship that sailed to Shanghi, China. The family lost contact during the war. My father [emigrated] to Palestine in the summer of 1939 since he could no longer stay in Britain under the Kindertransport arrangements after becoming seventeen years old. During the war he had voluntarily joined the Royal Navy in Palestine, serving as a sailor on a frigate.

My father spent less than a year at Whittingehame. However, this time was highly meaningful in ways that I came to appreciate only in recent years as I pursued my research on collective and private memory. Indeed, events occurring during early adulthood seem to have a particularly powerful impact on the rest of one’s life. My father, as I remember him, was an Anglophile. Although he was highly proficient in Hebrew, he adopted the English language as a mother tongue. Later I learned so did many of the kinder. He appreciated English literature and was much more comfortable in reading English than either German or Hebrew. He listened to the BBC on the radio, trusting it more than the Israeli media.

In those days Israelis were subjugated to the Zionist version of the ‘melting pot’ doctrine, which propagated total immersion and assimilation. The memory of the war and the Holocaust was to remain within the boundaries of the official narrative. Thus, keeping parts of his individual identity and clinging to them was quite unusual, not to say unacceptable. My father never talked in any detailed systematic manner of his experience, ‘in Scotland’. In those days, his generation hardly ever discussed their experience during the war. He never talked about the trauma of being forced to leave his family in such urgency and of the family practically being torn apart with no clear prospects for the future. Rather, he presented it as some kind of an adventurous experience - somewhat like an extended youth camp. He spoke about working on the farm, the cold winter with hardly any heating, the food and the fights among the children. He never set out to tell a full coherent story and I never really asked.

Thus, my father’s recollections came in bits and pieces. ...I attribute more and more of the daily routines and habits to his stay at the estate. It has a lot to do with the senses: taste, smell and sight. It is the way I was taught to cut the thin slices of bread, the thin cucumber slices, the bitter orange marmalade we had for breakfast rather than the red unidentified matter I saw at my friends’ houses and craved for, the meticulousness with which he had made tea, the black sauces he used with his food, all of which were obviously non-Israeli. As a child I could never understand his insistence on these ‘strange’ habits, which were so markedly distinctive. ...As a Balfour’s Bairn my father always longed to go back to Scotland and visit the Whittingehame estate, but never succeeded in fulfilling his wish. I am very contented and grateful to have been able to do so, with part of my family. After all, something of a Balfour’s Bairn is in me too and I cherish it.”

Dr Ruth Amir visited Whittingehame in 2001 to see where her father had stayed.

From the left - David Haire, Bob Mitchell, Ruth’s daughter, Lord Gerald Balfour, Ruth Amir, Ruth’s husband, Jack Tully Jackson

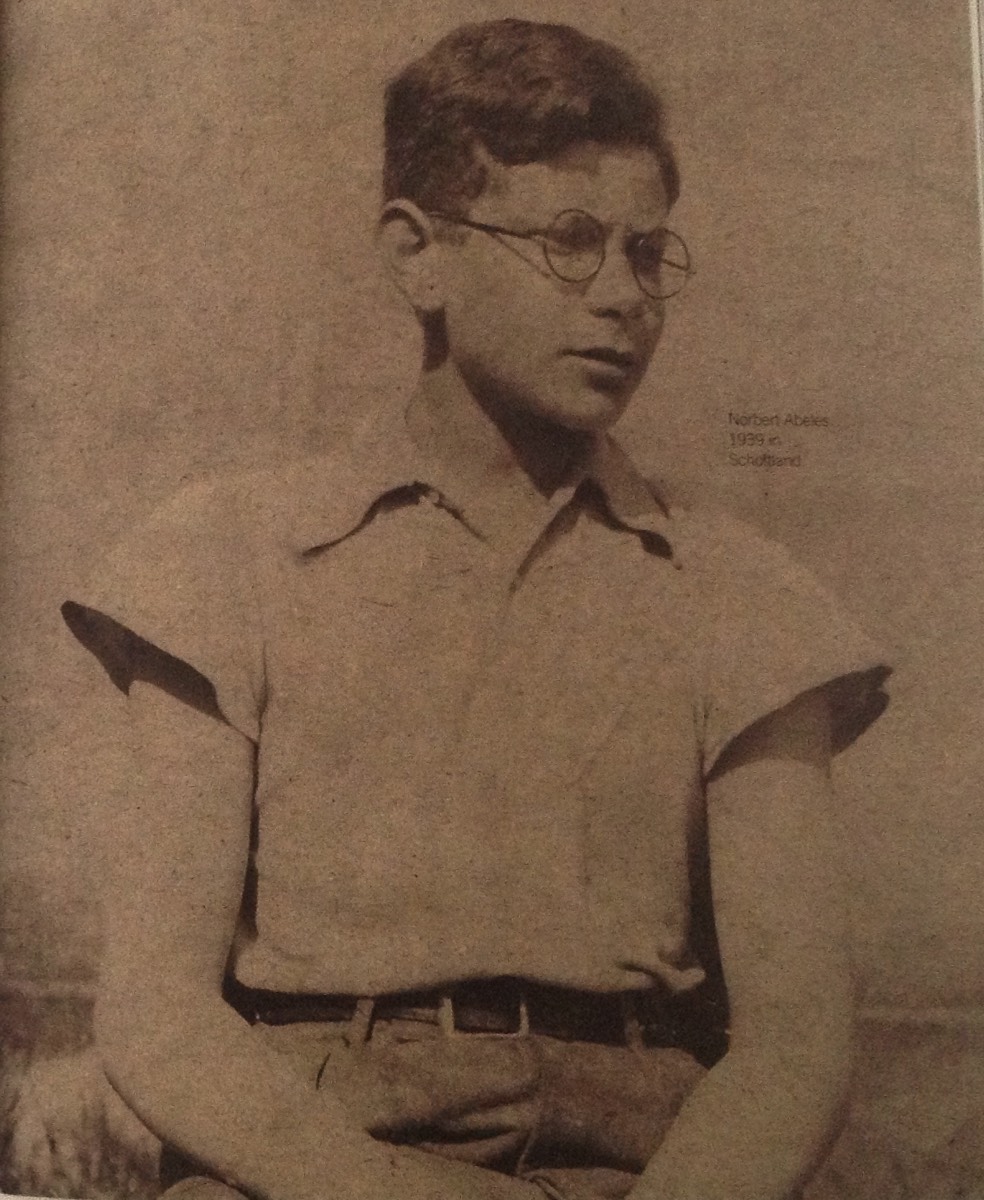

5. Norbert Abeles

Norbert Abeles was a pupil at Whittingehame Farm School.

Here he recounts his often vivid recollections of his time there.

Norbert’s Family

Norbert was born to liberal and assimilated Jewish parents in Vienna, Austria, in 1923.* His father, Siegfried, was a self-educated man from a working-class background who worked in the Welfare Section (Travellers’ Section) in the offices of the Jewish Community. As such he had to be careful that he was not seen to be offending religious laws by, for instance, eating non-kosher food, using the tram or smoking on a Saturday or being absent from services in the Synagogue. When he was a young man, he had taught the blind and the mentally and physically disadvantaged and was fascinated by old Jewish tales. He published three children’s books on the latter. Norbert’s father died in 1937 before the Anschluss.

Norbert’s uncle (his father’s brother), an invalid from World War One, and his non-Jewish partner were little affected. He died of natural causes in 1940. His adopted child was taken for forced labour to Germany and died in a bombing raid. Norbert’s aunt (his father’s sister) and her husband ran a small shop selling hats: both were killed by the Nazis. Norbert’s mother, Sabine Abeles (née Griffel) came from a middle-class family in Krakau (now in Poland) and she was deported on the sixth of May 1942 and killed five days later. An uncle (his mother’s brother) was killed by the Nazis in Croatia when they caught him after he had fled from Vienna.

Fortunately, a number of Norbert’s family escaped to Britain and survived. This included his mother’s brother (a physician), his wife and child as well as his mother’s senior sister and her daughter. His mother’s uncle and his non-Jewish wife and two sons likewise came to safety in Britain.

[*This means that while Norbert’s parents were Jewish, they were completed culturally integrated. In all external ways, they were like their gentile neighbours, in dress, habits, friendships, language, etc. etc.]

Norbert’s mother fell on hard times after her husband died as any ‘pension’ from his employer ceased after eight months. Norbert wrote, “Our fellow tenants in the three storey tenement behaved as usual, some said (confidentially) nasty things about the Nazis; only the daughter-in-law of the tenement’s owner was a conscious Nazi and she had my mother removed from the flat after I had gone to the UK.”

By 1938 conditions for Jews in Austria had visibly worsened. Norbert was not allowed to attend school after July 1938 and was physically assaulted on one occasion. However, since he didn’t look particularly Jewish, he normally managed to avoid such incidents. However, it was very difficult for many people, especially the poor, to obtain an exit visa. Many people simply did not have sufficient cash to pay for one in addition to the train ticket.

Kindertransport

When the news of the Kindertransport reached his family Norbert’s mother didn’t hesitate and arranged for him to leave. He departed on a special train from Vienna on the 10th December 1938 and after a day’s journey reached the Channel coast where he embarked upon the SS Prague. By daybreak he had reached England and safety.

Norbert’s Aunt